By Julia Berkman, Mollie Clements and Bianca Lancia

“It was a silent cry against senseless destruction; an affirmation of belief in peace and a disavowal of violence and anarchy. It was a plea for reformation rather than revolution, and in this sense it was the spirit of King,” wrote Western Front staff writer Bob Hicks, after nearly 2,000 people held a moment of silence on Western’s campus following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April of 1968. President Jerry Flora cancelled classes later that same day in solidarity.

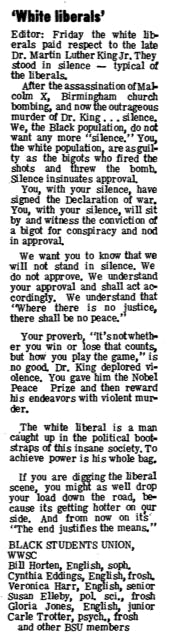

In a letter to the editor in the same issue of the Front, members of the Black Student Union decried the demonstration and said it was ironic that the crowd -- which was predominantly white -- were silent on issues of race yet again.

The letter received backlash from several letters to the editor published in the April 30, 1968 issue, but also resounding support from community members.

“How dare you condemn Black people for using violence as a way to take their freedom. You should be screaming at the system which makes them have to use violence,” wrote Rebecca E. Bathurst, a sociology-anthropology major.

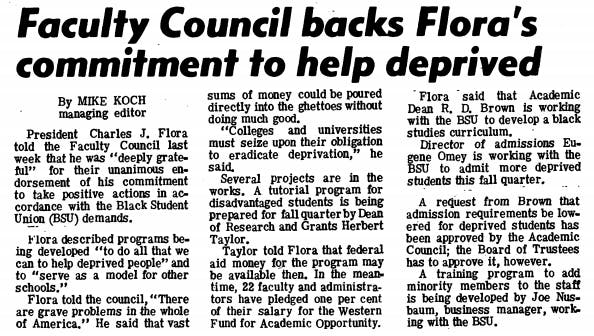

As civil rights activists around the country began to demand more anti-racist action from their university administration, activists at Western were no different. In May of 1968, Flora was given a list of demands by the Black Student Union and a four-day deadline. Two days passed before Flora accepted all of the demands, according to an article from The Western Front published on May 21, 1968.

The Black Student Union said Western needed Black curriculum, Black faculty members and a committee to investigate racism on campus.

The demands were supported by the Associated Students President at the time, Noel Bourasaw.

"We are racists by default,” he wrote in a letter to Flora that expressed his support for the Black Student Union.

Response to the Black Student Union’s demands were lukewarm from the wider white community. Some thought the language and tone used in the article was too harsh, according to several letters to the editor sent in May of 1968.

In an editorial written by copy editor Donald B. Wittenberger, The Western Front threw its support behind the Black Student Union and its demands.

“It makes no difference whether the BSU's desires are ‘requested’ or ‘demanded;’ the language is unimportant. What is important is that greater understanding of Blacks by whites be achieved. For this reason, this editor feels the BSU's goals for this campus are both reasonable and relevant.”

Donald B. Wittenberger

In a Western Front editorial written by George Hartwell and Libby Bradshaw in 1970, the Black Student Union said that there were 120 black students enrolled at Western at the time, 2 percent of the overall population. The editorial argued that Western’s unfair admission policies were to blame.

“The persistence of institutional standards like those of Western's Admissions Office can only serve to widen the division between races, classes and cultural groups,” the editorial read. Then-Admissions Director Eugene Omey said that admissions was actively trying to recruit minority students in 1970. According to an article from a 1970 edition of the Western Front, the admissions office hired a student from the Black Student Union to act as a liaison between potential students and the school.

In Fall of 2018, Western reported that almost 3 percent of the incoming freshman class was black. According to an evaluation done in 2014 by the Taskforce for Diversity and Inclusion, only five tenured professors at Western are Black.

The demands and concerns put forth by the Black Student Union in 1968 aren’t that different from the demands made by students of color on campus during a community forum on Dec. 6, 2018. According to an article from The Western Front on Dec. 10, 2018, attendees of the forum brought up hiring and retaining more faculty of color, as well as the creation of an Ethnic Studies college as two main goals they would like Western’s administration to aim for.

However, following the forum, Black students felt like they were underrepresented by the demands put forth at the forum. In a statement released on Dec. 9, 2018, Black students voiced their concerns with how the forum had gone.

"We release this statement for everyone at Western Washington University to realize the privilege they have to be able to speak over Black voices, especially our peers with in the ESC. We reach out for everyone to understand that this is not an attack or a personal vendetta, but this is only how most of the Black students felt about the forum. This is how Black students feel every single day at Western."

"We want to acknowledge the erasure of our voices within the forum and the walk out. We also recognize that we are a minority of the minority within the Ethnic Student Center," the statement read. "The forum and demands went into all kinds of other student issues that we see important as well, but didn't completely address our needs as a Black community. Historically we are used to perpetuate any movement other than our own. There was no focus on the fact that there are students who are fearful for their safety and their lives."

According to the university website, Western administration has vowed to stay true to a set of values regarding public expression and assembly. These vows include the commitment to a safe campus environment, a belief that every voice matters, to seek to understand and to engage with people in protest.

** This post was updated to reflect the fact that the needs and experiences of Black students and students of color are often conflated, but not the same.