Content Warning: This article discusses incidents of anti-Asian violence and bigotry.

Speakers at the Racial History of Whatcom County panel discussed the importance of understanding the history of anti-Asian racism in the region at Bellingham Technical College on May 9.

The panelists included Josh Cerretti, associate professor of history at Western Washington University and racial history tour guide; Neah Ingram-Monteiro, librarian at Western; Michael Karlberg, professor of communication at Western; and Vernon Damani Johnson, former professor of political science at Western.

Hannah Simonetti, the director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at Bellingham Technical College, served as a moderator.

“A lot of the white folks in Bellingham thought that whiteness in Bellingham was a historical accident,” Karlberg said during the panel. “The whiteness in Bellingham was by design.”

Karlberg co-created the Bellingham Racial History Timeline, a website that documents the history of discrimination that led to the city’s current lack of diversity. A Diversity & Social Justice Grant from Western helped fund research for the site.

For Ingram-Monteiro, her community’s lack of awareness of historical anti-Asian racism is personal. She described growing up as a South Asian person in Bellingham as a great experience but added that colorblindness and internalized racism were parts of her childhood in the city.

Ingram-Monteiro said she only learned about Bellingham’s anti-Sikh riots when she went to Berkeley, California. She talked to descendants of Sikh immigrants who fled the Pacific Northwest because of racist violence.

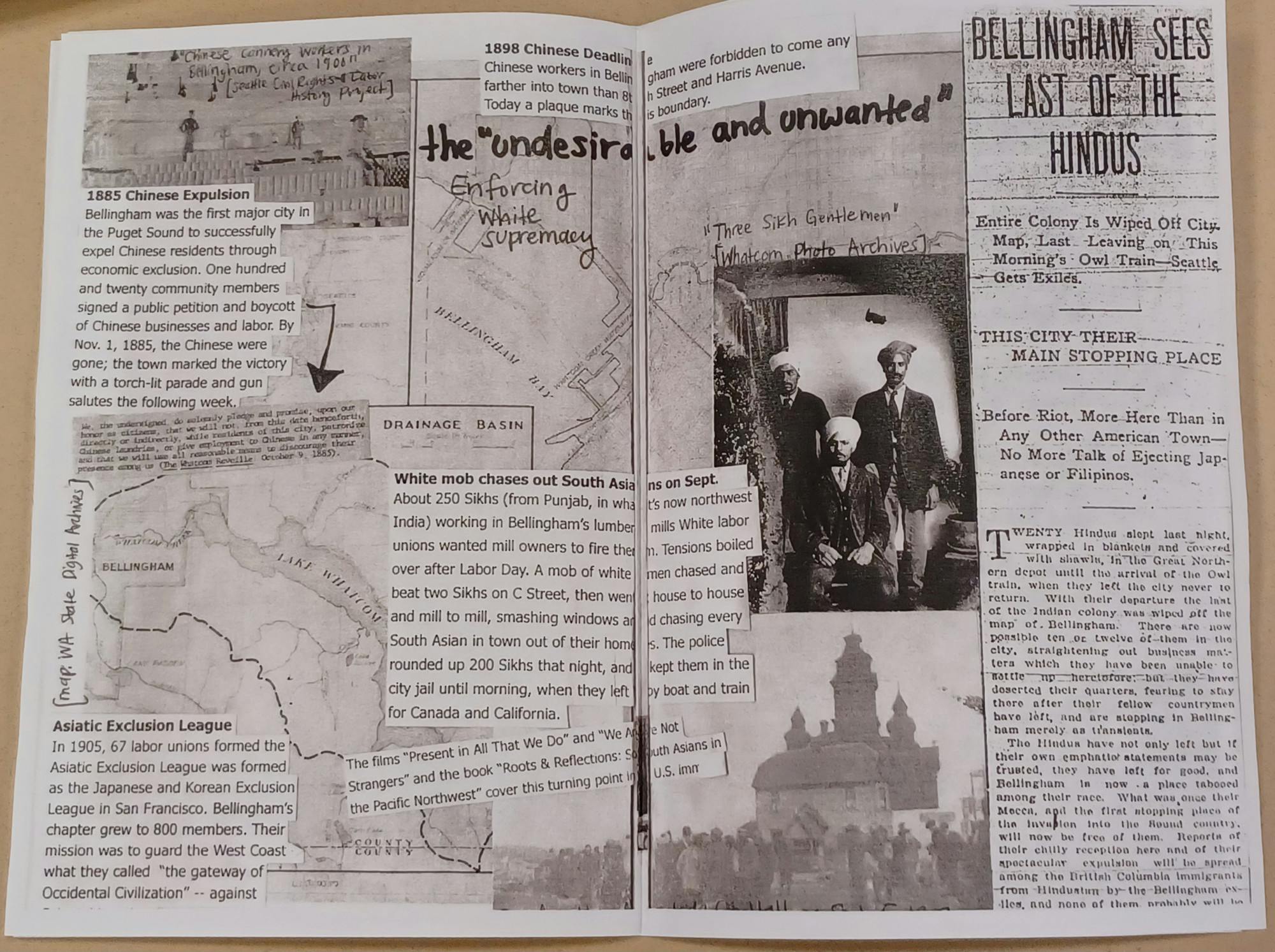

In the early 1900s, many Sikh immigrants from the Punjab region of India settled in Vancouver, British Columbia and later in Bellingham, triggering a backlash from working-class whites. After Sikh mill workers failed to meet their demands to leave Bellingham by Labor Day, white workers ransacked Sikh homes and workplaces, driving them out of the city on September 4, 1907.

Ingram-Monteiro said the Bellingham violence was part of a wider racist movement along the West Coast called the Japanese-Korean Exclusion League, which was later renamed the Asiatic Exclusion League to reflect hatred against a wider range of ethnicities.

“I feel like with Bellingham we have this big gap in our history because these communities have been kicked out time and time again, compared to a city like Seattle or Vancouver where there’s really vibrant Asian communities,” Ingram-Monteiro said after the panel.

During the panel, she used an example of an anti-Sikh headline used in a 1906 Puget Sound American newspaper article to show how historical media resembles modern rhetoric about immigrants taking white jobs.

Anti-Asian racism in Bellingham and the wider U.S. was institutionalized with the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned further Chinese immigration to the U.S. for 10 years. It was the only U.S. immigration law to specifically target one ethnicity.

Karlberg said white residents boycotted Chinese-owned businesses in Bellingham, forcing Chinese immigrants to leave the city in 1885.

Karlberg said Bellingham residents should look at this history at two levels. First, they should understand the immediate suffering of Asian immigrants who were expelled from the city. Second, they should consider what the city would have become if white people had co-existed with Indigenous and Asian people instead of driving them out.

“Bellingham would be among the most diverse multicultural cities you could find anywhere on the continent,” Karlberg said. “We would be a remarkable place. Bellingham itself was robbed of the opportunity to become really a gem of a city.”

The panel also discussed the racially-motivated 1942 internment of Japanese Americans after Pearl Harbor. Many of the interned Japanese were U.S. citizens, said Karlberg.

Cerretti said a former Western student named James Okubo was one of about 33 Bellingham residents of Japanese descent to be forcibly removed from their homes and interned at the Tule Lake War Relocation Center in California. Okubo dreamed of becoming a dentist and his family owned the Sunrise Cafe on Holly Street.

After Okubo died in a car accident in 1967, he was posthumously awarded a Medal of Honor for his army service during World War II and an honorary degree from Western because he was interned before he could finish his studies.

Cerretti said Japanese internment was an example of ideas of national security being used to justify racial discrimination in the U.S.

Many communities of color in the U.S. face pressure to join the military for college tuition, social status and belonging, according to Ingram-Monteiro. People often learn about Okubo through his role in the military.

Ingram-Monteiro was the former executive director of the Whatcom Peace & Justice Center, an organization that advocates for nonviolent government policies and alternatives to military service for young people who seek to fund their college education.

While the panel primarily focused on the local history of Asian Americans, it also discussed discrimination against Black and Indigenous communities in Bellingham.

“You can work [in Bellingham], you can have a job here, but don’t let the sun set on your behind in the town,” Damani Johnson said.

He said Bellingham was a “sundown town” where law enforcement drove Black people to the city limits and told them to leave after dark. The Ku Klux Klan held a march through downtown Bellingham on May 15, 1926 after the city’s Tulip Festival parade did not allow them to march there.

The panelists emphasized the role historical knowledge plays in creating a more equitable future in Whatcom County.

Karlberg said he did not co-author the site for Bellingham residents to beat themselves up about the past, but rather as a tool for thinking about the future of racial justice advocacy.

“Hearts and minds are half the equation of addressing racism in this country,” Karlberg said. “Policy is the other half.”

He said recent research found people are indoctrinated into white supremacist groups because they feel isolated, but they are able to leave those groups by forming relationships with people outside the group.

After a cross was burned near a camp of Latino migrant workers in Lynden in 1994, Damani Johnson helped found the Whatcom Human Rights Task Force. He said the organization advocated for the Whatcom County Council to form a Racial Equity Commission, which they voted to create in October 2022.

“These projects of white supremacy that were oriented toward genocide have all failed,” Cerretti said.

One of the first stops on Cerretti’s racial history walking tours is the Centennial History Pole in front of the Whatcom County District Court. The base of the pole, carved by Joe Hillaire in 1953, depicts two Lummi men rowing the first two white settlers in Bellingham Bay. Cerretti said the settlers’ lack of paddles represents the Lummi peoples’ resilience and knowledge of the land they inhabit.

“We’re providing an education to our students that helps them dismantle white supremacy,” said Simonetti.

While the panel discussed the racial history in Whatcom County, racism is not confined to the past. Stop AAPI Hate, an organization formed in March 2020 in response to anti-Chinese rhetoric about COVID-19, reported 11,467 anti-Asian hate incidents between 2020 and 2022.

As Western and the wider Bellingham community continue to celebrate Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Heritage Month, efforts like the Racial History of Whatcom County panel highlight the need for historical knowledge as a tool to address contemporary racism.

Western will host a series of events to celebrate APIDA Heritage Month.

Mia Limmer-Lai (she/her) is one of two copy editors for The Front this quarter. She is a second-year environmental studies and journalism student at Western with a minor in honors interdisciplinary studies. In her free time, she enjoys reading books and listening to punk music. You can reach her at mianlimmerlai.thefront@gmail.com.