By Jack Taylor

Cascading down from Mount Baker before flowing into Bellingham Bay, the Nooksack River is the sole river stemming from Mount Baker. As it meanders over 70 miles, the river provides for each community it touches.

However, despite being a cherished part of local Native American culture, the river is experiencing the impacts of climate change.

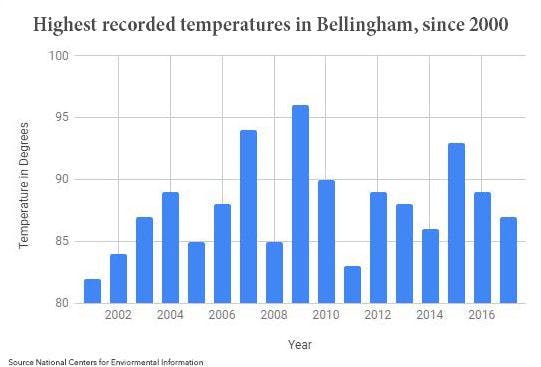

Overall temperatures across the globe are rising, according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. This change has been most notable in recent decades. The 10 warmest years have all occurred since 1998.

Western Environmental Science Professor Robert Mitchell specializes in hydrology, the study of water on the earth.

Mitchell’s current work examines the physical changes in watersheds from warmer climates. He has recently worked with the Nooksack Tribe to see how the changing climate is influencing salmon habits in the river.

Mitchell said the root of the issues starts on Mount Baker.

Having a smaller amount of snow during the winter seasons will create a faster water flow during the winter months. This could create more floods, Mitchell said.

During the spring and summer, the result is opposite: the stream flow of local rivers would wane as mountain temperatures rise due to less snow.

Given the river’s glacial origins, Mitchell believes the Nooksack will continuously rotate through this cycle.

The salmon in the river will pay the price.

The salmons ability to reproduce depends entirely a certain amount of sediment that, if floods were to happen during winter and not spring, will be washed away before salmon reproduce in the summer, Mitchell said.

According to Mitchell, water temperature is also a large influence on a salmon’s reproduction. If temperatures get warm enough, their ability to spawn, breed and produce will diminish, Mitchell said. Less salmon will spell trouble for many communities.

“A lot of our Pacific Northwest economy, especially for the tribes, is reliant on salmon. It is a huge industry for the tribes economically speaking, as well as culturally. It is a part of their history and culture,” Mitchell said.

According to a 2010 survey conducted by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, commercial fisheries in the state generate an average of 1.6 billion dollars annually. Additionally, around 40 percent of Washingtonians partake in outdoor economy such as fishing and observing wildlife, providing 14,000 jobs in the state.

“What we are doing right now is changing the geochemistry of the planet in a way that will still be in motion thousands of years from now,” Western geology professor Andy Bunn said.

Bunn said the returning carbon will impact the temperatures of the oceans and heat the water up.

“If we were to shut off the carbon sources to the atmosphere right now, those temperatures in the atmosphere will go up for another thousand years before going back to leveling off,” Bunn said.

Bun recommends society stop looking for instant changes and start thinking about long term change.

“We often focus on what we can do, like I can ride my bike more often, or I can drive less, or can I eat less meat,” Bunn said. “Those are all things that are good for your own personal carbon footprint. However, what really needs to happen is a global action.”

Bunn believes calling local legislatures to ask about policy changes is one the most effective methods one can do to help create change.

Change can start on campus.

Western environmental policy student and Zero Waste Coordinator Hope Peterson said being environmentally conscious can start on campus.

“Utilize composting, as well as walking or busing to campus instead of driving, and just being conscious of your consumerism, so trying to buy things with minimal packaging and things produced locally,” Peterson said.

Peterson believes the greater impact in thinking green is the influence it will have on lower economic communities.

Citing how greenhouse gas emissions and landfills negatively influence areas of lower economic status, Peterson gets encourage through knowing that being green helps more than just her.

“To know that the work that I am doing could maybe lessens some of the hardships that those communities are going through makes me feel better,” she said.