Since the first Earth Day in 1970, events around environmental protection have evolved. Originally, more than 20 million participants were involved — to some degree — in protests, marches and other events across the nation, fighting to create political change. Their impact would be felt for years to come.

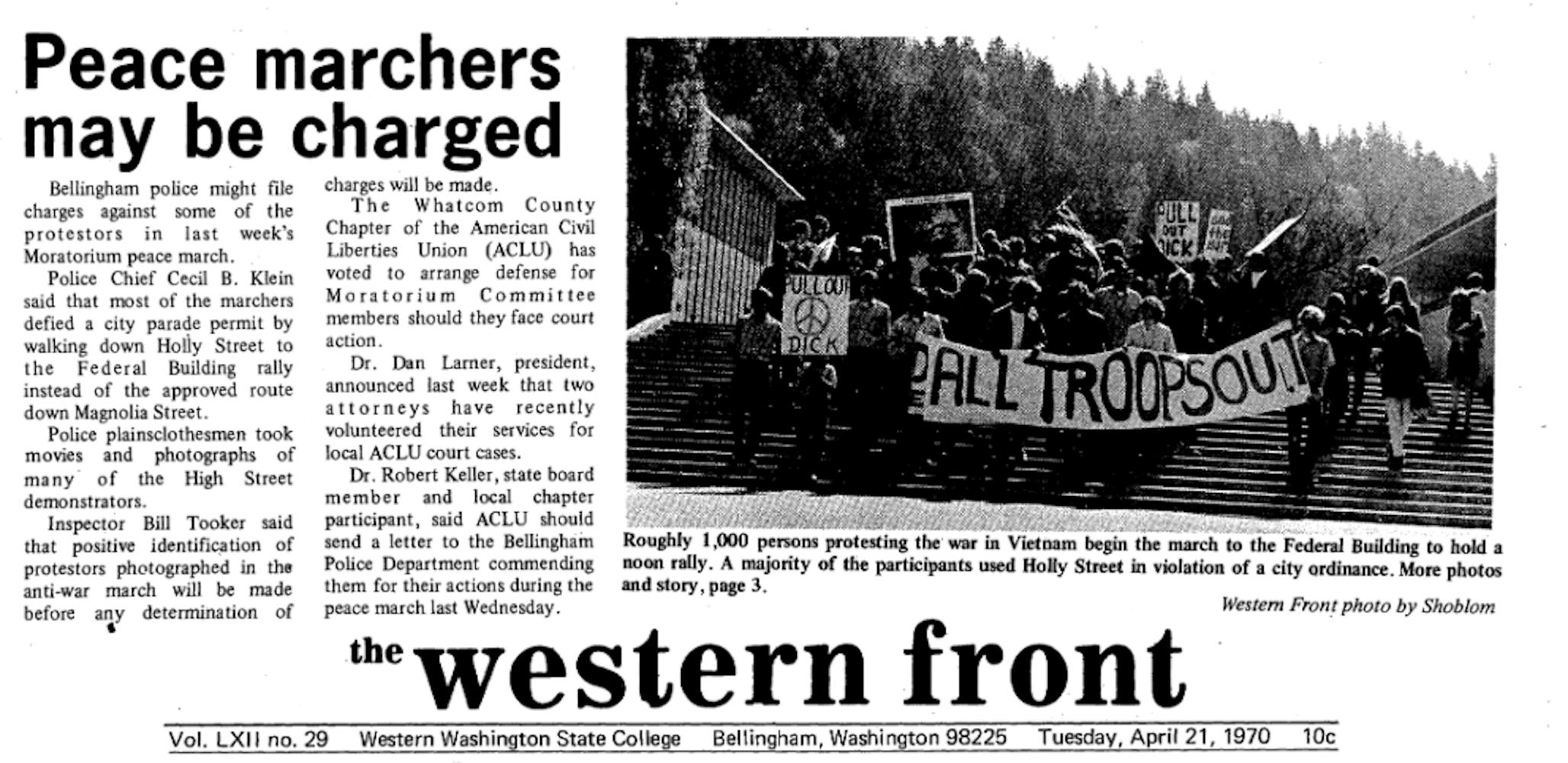

The first Earth Day was the largest single-day protest to date, according to The Weather Network. Protestors’ demand for environmental change spurred politicians into action.

“That is a show of force that says if you do right by these people, you will be reelected; if you do wrong by these people, you will be gone,” said Mark Neff, associate professor of environmental policy at Western Washington University.

Later that year, former President Richard Nixon, under pressure from the Earth Day movement, started the Environmental Protection Agency. The EPA oversaw the formation of states’ environmental plans.

Following this, three new pieces of legislation, which still dictate the U.S.’s approach toward the environment, were passed: the Clean Air Act of 1970, the Clean Water Act of 1972, and the Endangered Species Act of 1973.

Neff said that Earth Day was born from a “window of opportunity” left by significant events and societal trends.

Environmental disasters caught national attention, such as the waste-filled Cuyahoga River, which runs from the Great Lakes through Cleveland, Ohio, which caught fire in 1969 for the 10th time in the last century.

“It is quite a statement when water catches fire,” Neff said.

Curt Rowell was a student at Western in 1970 and active in the anti-war movement. He saw many articles concerning environmental issues in the local anti-war underground newspapers, such as the Northwest Passage, a paper dedicated to investigating political and environmental issues in Bellingham and the Pacific Northwest.

Rowell recalled the Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969, the largest oil spill in U.S. waters at the time. "[The oil spill] was maybe the biggest national catastrophe on the environmental front. That was fueling the sense of urgency. A lot of people felt it," Rowell said.

The urgency Rowell explained is the sense of impending doom many felt before the first Earth Day.

Other factors in the creation of Earth Day included images of the Earth taken from the Apollo missions, which allowed people to see the Earth as vulnerable and finite. Influential environmental novels like “Silent Spring” and “The Population Bomb,” the latter of which is based on racist ideas, also factored into Earth Day’s creation.

In the industrial age, environmental damage was the cost of doing business. But, by the mid-20th century, the country was wealthy enough to afford to do things differently, said Neff.

In the wake of these events and trends, former Wisconsin senator Gaylord Nelson recruited a Harvard graduate, Denis Hayes, to coordinate teach-ins around environmental concerns. These plans for relatively small educational campus events developed into the nationwide movement of Earth Day.

Neff teaches his students that Earth Day brought together people of all demographics: those concerned with labor and jobs, racial equity and the environment.

There was a sense of unity, and even more than that, urgency, in protecting the environment.

“[People] felt like [they] were a part of something bigger,” said Neff.

However, Neff doesn't believe Earth Day has had the same political influence since then. He said one explanation for this is environmentalism has become a partisan issue.

In the current political climate, many see the change in a "greener" direction as a move toward employment issues for specific industries, like oil or mining.

“Anyone who sees their job as potentially vulnerable to policy changes has a pretty direct incentive to say, ‘Environmentalism is not for me,’” said Neff.

While Earth Day events have not triggered the same direct political action as they once did, communities still put their efforts towards caring for and educating others about the environment every April 22.

Western’s Sustainability Engagement Institute has put together a week of Earth celebration. The institute directly facilitated five events, encouraged clubs to host their events and offered funding opportunities to the clubs.

In all, 25 events are attached to Western’s Earth Week this year.

“Staying focused on sound policy and organizing people’s collective voices for marginalized communities are two important activities that can help keep Earth Day central in our minds beyond the actual day,” said Eli Wheat, lecturer of environmental studies at the University of Washington.

In years following the original Earth Day, some have felt the celebration lacked equal representation of diverse voices.

Western students are trying to change this.

The Intersectional Ecofeminism event held on Tuesday, April 18, consisted of a discussion of environmental justice education and awareness.

Panelists Diandra Marizet Esparza, co-founder of Intersectional Environmentalist, and Jarre Hamilton, who oversees research development at Intersectional Environmentalist, were joined by Sylvia Hadnot, Western instructor, and Maiyuraq (Lauryn) Nanouk Jones, a Western student and member of the Native American Student Union.

The event also had free food from Calypso Kitchen and musical performances from Kitty Obsidian and Abby Louise.

"A lot of people in the room, just from overhearing chatter and watching everybody's reactions, felt pretty empowered by the discussion,” said Ave Hamilton, a first-year Western student.

Erica Richardson, Earth Week Event Coordinator, said food injustice was the central theme of this year’s Earth Week.

“We didn’t set out to have [food injustice] be [the theme], but there definitely seems to be a lot of emphasis on that,” said Richardson.

Sustainability Engagement will be showing three documentaries about food inequality. They will also be giving free food away at multiple events to encourage attendance and take care of those who attend.

The City of Bellingham has its own Earth Week planned. Events include a volunteer work party to restore the Sehome Arboretum and a photo competition called the Essence of Bellingham, which offers a Climate Action Award.

Essence of Bellingham recurs annually and takes submissions from amateur to professional photographers.

“I think the goal was to engage the community in a fun way and show off the beauty and uniqueness of this area,” said Rochelle Parry, who received the Climate Action Award in 2022 for “Street Surfing” — an image of flooding in Squalicum Parkway, Bellingham.

For this year’s contest, photos can be submitted online until May 1.

“The City of Bellingham’s Earth Week activities provide opportunities for community members of all ages to learn about, celebrate and restore our environment,” said Stefanie Cilinceon, the City of Bellingham’s environmental education and outreach specialist.

Earth Week initiatives by Western and the City of Bellingham preserve values from the original Earth Day.

“A takeaway [from the first Earth Day] that we need to remember is that environmental concerns can have very broad appeal. They did. [Participants’] passions were real, and they were directed at protecting the human quality of life and non-human quality of life. It's still there,” said Neff.

Eli Voorhies (he/him) is a fourth-year student at Western in the visual journalism program. Now serving as the photo and video editor, he has worked two previous stints as a Front editor and interned for Cascadia Daily News. Outside of the newsroom, he rock climbs and loses track of time in the photography dark room on campus. You can reach him at eliv.thefront@gmail.com

Ben Delaney (he/him) is a city life reporter for The Front. He is a junior majoring in environmental studies journalism. In his free time, he enjoys skiing at Mt Baker, fishing on local rivers, and just spending time outdoors. You can reach him at delaney.thefront@gmail.com.