Homelessness and affordable housing are deeply intertwined topics. According to a residential survey conducted in 2016, homelessness is the top challenge facing Bellingham, followed closely by affordable housing.

Kristen Branson is a housing case manager at the Opportunity Council, a community action agency that offers different services and resources for homeless and low-income individuals and families.

“There’s a huge housing crisis that people who are housed just don’t identify with,” Branson said.

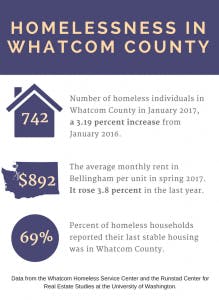

There were 742 homeless individuals in Whatcom County in January 2017, according to the “point-in-time” count conducted at the start of each year by Whatcom Homeless Service Center.

Branson said demand for their services increases as temperatures decreases.

“It gets a lot more heightened in the winter,” Branson said. “It’s a lot more frantic and urgent, panicky for everyone. It’s very stressful when it’s cold outside and there’s nowhere to go.”

A shortage of long-term and short-term housing limits options for people looking to find shelter.

“A lot of the housing in Bellingham is geared toward students, which is very frustrating,” Branson said.

Brittany Nicholl, case manager lead at the Opportunity Council, helps place clients in homes and assist in the renting process.

Nicholl said the housing market in Bellingham leads to a lot of frustration when trying to place clients in homes and she’s seen a decrease in the availability of housing in her 2 ½ years at the Opportunity Council.

“That’s our biggest barrier right now, the lack of affordable housing and the really steep rental prices that we’re finding,” Nicholls said.

The average monthly rent in Bellingham was $892 per unit in spring 2017, and rose 3.8 percent in the last year, according to a report by the Runstad Center for Real Estate Studies at the University of Washington.

Another struggle is finding landlords and rental companies that will accept their clients, despite support the council offers, Nicholl said.

“There’s a notion that people who are low-income and on a housing program are gonna have huge barriers and destroy the unit,” Nicholl said. “In our programs we’re working really hard with our clients to work on their goals and achieve stability.”

Even with housing assistance programs like the ones offered at the Opportunity Council, which pay for a portion of rent, inspect units and do regular check-ins with clients, many still find themselves struggling to find a home.

“Sitting here with my clients looking for housing can be really discouraging. It’s hard to be that bearer of bad news,” Nicholl said. “People get a lot of no’s, and I can’t imagine what that feels like as a client, to hear that constant ‘No, we don’t work with your programs,’ or ‘We’re not willing to give you a chance.’”

Earlier in the year, an emergency homeless shelter was proposed in conjunction with the Lighthouse Mission Ministries and the city. Mayor Kelli Linville, on behalf of the city, offered the Port of Bellingham $300,000 to not purchase the land they wanted to build the shelter on.

The Port of Bellingham bought the site in a last-minute move, blocking the shelter to maintain the current atmosphere for businesses at the location.

“People don’t want to talk about it. They don't want to build a shelter because they don’t want it in their backyard,” Branson said, “You can’t build a homeless shelter out in the county because there are no services there. There’s no access to the things people need. It has to be here.”

Andrea Northey works with the Homeless Outreach Team through the council. The team goes out into Whatcom County and makes connections with members of the homeless community, bringing coffee or offering to connect them with available services.

“We try to familiarize ourselves with everyone who’s experiencing homelessness. Our main goals are to engage with people where they are,” Northey said.

Northey said there are plenty of misconceptions people have when considering those who are homeless.

“People think people get sent here a lot, because we have more services. Maybe occasionally that happens, but it’s not the majority of the time,” Northey said.

In 2017, 69 percent of homeless households reported in the “point-in-time” count that their last stable housing was in Whatcom County.

Northey said providing more low-income housing and resources would be a step in the right direction toward ending homelessness, as well as individual efforts to humanize those going through rough times.

“There are a hundred different reasons why someone would be homeless and it’s a very complex issue so it’s hard when people just kind of blame the person for their circumstances,” Northey said.

For Branson, a community response and acknowledgement of the issue is also what she would like to see.

“I think if more people got out and actually had conversations with the folks that are outside, they would see that they’re just like the rest of us. They’ve just fallen on bad times,” Branson said. “People are people. Everywhere.”