Local providers and politicians convened on Sept. 17, 2024, to identify solutions for Whatcom County’s ongoing opioid crisis. The Joint Behavioral Health & Legal and Justice Systems Committee meeting outlined two crucial initiatives to address gaps in the community’s social service continuum.

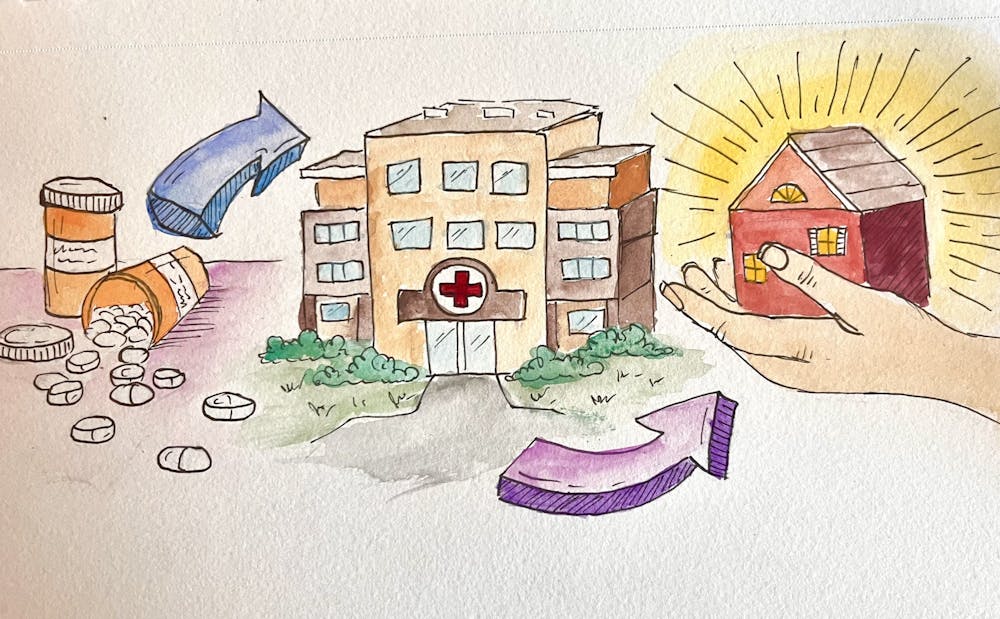

Immediate Priorities: Expanding Treatment and Housing

The first major initiative discussed at the meeting focuses on increasing access to opioid treatment in urgent care settings. PeaceHealth has independently begun piloting the use of buprenorphine, a medication proven to reduce overdose deaths, though underutilized nationwide.

Dr. Shannon Boustead, a family doctor at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center and medical advisor to the Behavioral Health Committee, emphasized the importance of expanding access to buprenorphine. He is advising Whatcom County’s opioid response, and PeaceHealth is the largest medical provider in Whatcom County.

“We’re figuring out how to leverage our available resources in this community to meet the very challenging need of opioid use disorder (OUD) by increasing [access to] treatment,” Boustead said in the Sep. 17 meeting.

Boustead’s quotes and all others in the story come from the same meeting.

PeaceHealth has decided to take the reins and pilot the usage of buprenorphine nationally in hopes that other hospitals will follow suit. They have pledged to work towards halting the largest drug crisis in American history.

The second urgent topic discussed was finding housing for those in outpatient treatment programs. In a separate initiative, the Opportunity Council raised $60 million this year to construct 120-130 permanent affordable housing units off Bellis Fair Parkway, addressing the urgent need for supportive housing. These units aim to provide stability for income-restrained individuals and families, particularly those transitioning from treatment programs.

Addressing Gaps in Urgent Care and Outpatient Support

Currently, hospitals often discharge patients with OUD after monitoring them, leaving them to seek treatment independently. PeaceHealth’s pilot program aims to change that by providing medications directly in urgent care.

“Instead of hospitals just monitoring someone for safety and then telling them to go find treatment, [offering these medications] means providing real solutions and treatment plans for real people,” Boustead said.

The pilot aligns with findings from the National Institute of Health, which highlight the potential of buprenorphine to decrease overdose deaths. It is no easy feat for hospitals to develop protocols to administer this medication — especially within a public healthcare system where non-fatal overdoses aren’t technically reportable and opioid treatment programs have low retention rates.

“There’s a 30% success rate of patients staying in programs for one year nationally, but if they have housing instability or underlying mental conditions, it’s even harder to enforce,” Boustead said.

Boustead acknowledged the difficulty of monitoring patients and extending healthcare accessibility post-treatment. These are relative unknowns in the healthcare world since hospitals haven’t had the time or resources to pioneer this kind of programming. But post-treatment healthcare has the potential to make a huge difference.

Meanwhile, residential treatment facilities, such as Lake Whatcom Center, struggle with limited capacity. With only 16 beds, employees at Lake Whatcom Center said patients are often discharged to temporary shelters, tenant housing or the streets after 90 days of treatment.

“We take a lot of clients who are unhoused or newly out of jail,” said Andrew Hovenden, manager of outpatient programs at Lake Whatcom Center. “That 90-day window is simply not enough time.”

The Housing Crisis and Its Impact on Recovery

Hovenden believes one of the biggest challenges in outpatient treatment is his patients’ access to supportive housing.

“Ninety-nine out of 100 unhoused clients say, ‘I just need somewhere to live,’” Hovenden said. “That’s a programmatic gap in our community… there are just not enough beds.”

Without stable housing, patients face significant barriers to recovery. Although Whatcom County offers some permanent housing options, such as 22 North, Lydia Place and the YWCA, the demand far outpaces supply. “Additional people are becoming homeless as fast as the system can find available homes to them,” as noted in a recent report from the county’s Health and Community Services program.

“We’ve recognized for a long time that housing comes out in every conversation when it comes to stabilizing people,” said Bellingham City Council President Dan Hammill.

Despite the Bellingham Home Fund providing $4.9 million annually for housing and social support, it’s still insufficient in quelling the city’s ongoing homelessness issue, which works in conjunction with the opioid and fentanyl epidemics.

A Collaborative Path Forward

Despite limited local funding, Whatcom County maintains a substantial collection of behavioral health and addiction treatment programs. They aim to divert individuals from the criminal justice system by providing adequate healthcare.

“I’ve been here for 13 years, and this is the closest we’ve been to connecting the dots and changing things in a meaningful way as a community,” Boustead said.

With collaborative efforts underway to integrate healthcare and social services, Whatcom County aims to make lasting progress in its ongoing battle against the opioid epidemic.

“The dream is to create care access opportunities [for those struggling with OUD] throughout the continuum–ER, clinics, even primary care providers,” said Malora Christensen, health division manager of Whatcom County Health and Community Services.

Ella Gage (she/her) is a writer for the Opinion section. She's previously written culture-oriented articles for WWU's Rage Mag, as well as investigative environmental articles for the Whatcom Watch. She's a senior minoring in Journalism-Public Relations with a major in Communication Studies. In her free time, she loves good books, good concerts and getting outside. You can reach her at ellagage.thefront@gmail.com.