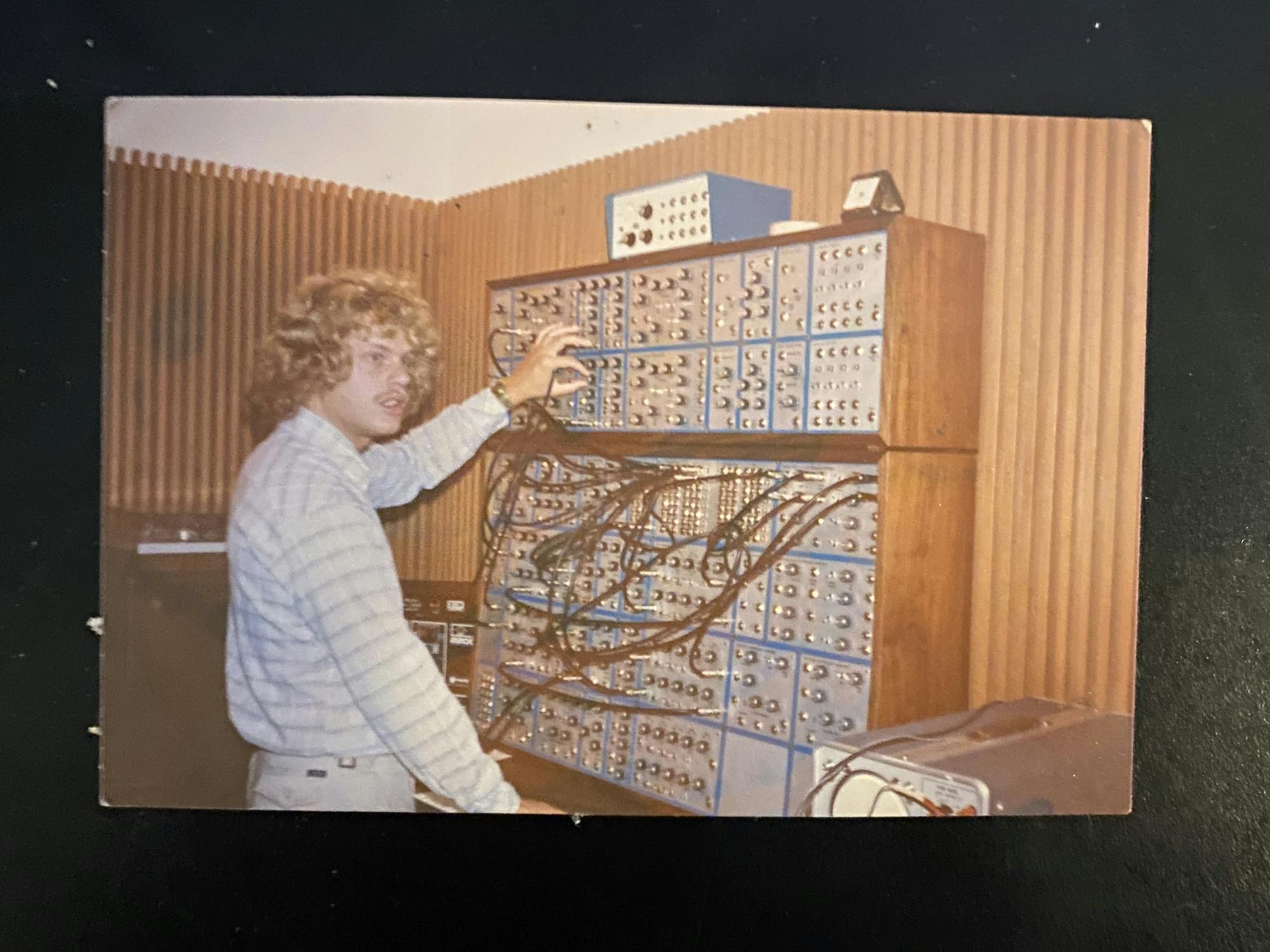

The walls are lined with documentary posters, band promotions and photographs of smiling musicians where “Binary Bob” Ridgley points out celebrity connections and local legends. From a synth band to the studio, Ridgley has been a musician his entire life. In 1989, he brought Binary Recording Studio to Bellingham, where its audio and film production have been a driving force behind the creative community.

Q: How did your interest in recording begin?

A: I played in bands and got good enough to start playing on other people's albums. I wasn't interested in anything but experience from other musicians. That's how I started living in the studio. I learned from a lot of people how to run this equipment and what makes a good record. Monkey see, monkey do.

I was playing in the bars when I was 18, 19 years old, in traveling bands. In college, I thought I wanted to be a jazz player, but I figured out pretty quickly that rock music was easier to make money. I studied some of the first synthesizers and got good at that. I didn’t start mixing music until the ‘80s. Then I bought this place in ‘89 because I wanted to build a studio here.

Q: How did Binary Recording Studio start?

A: I started Binary as a record label to support the synthesizer band that I was in, but all the other musicians I was around were also trying to produce. So I thought, why don’t we collaborate to help each other out? I was producing people all over the place, and that was another reason to build my own studio, so I could have the musicians come here instead of spending money in other studios. Eventually, people in the area heard about it, so I opened it up to anybody. The record label drifted away, and it became a recording studio. That’s one thing at Binary, we’ll take anybody in because everyone’s at a different level. You’ve got to start somewhere.

Q: How long were you traveling as a musician? Was it difficult to transition from traveling to being in the studio?

A: There’d be spurts, I think the longest was six years. I was getting burnt out. It’s a fun party scene in the bars and staying in hotels, but after a while I couldn’t do it. I didn’t think I was progressing any more, I was just doing a job. In the studio, you keep growing your art.

Q: On growing your art, what was it like to learn the technical aspects of recording, like equipment and balancing sound?

A: Of course you have to know how this stuff works, but that’s the smaller part of the whole picture. It’s how you hear things. I’d been doing this for about 20 years, and then one day I was sitting there and it was like a light bulb came on. I was listening to things differently, I finally figured out how the frequencies fit together. It has nothing to do with the equipment other than my ears. People say the best thing an engineer can do is listen. It makes a difference, how you hear the sounds, because you’ve got to figure out how you’re going to make it work. It’s not easy.

Q: How has technology changed the recording process over the years?

A: I started recording on tapes, and now we’re all digital. It’s the same concept, just different tools. When we were limited to a certain number of tracks, we had to make it work. Now you can record it all and figure it out later, now we have hundreds of tracks. A lot of music is pasted together like a crossword puzzle. To me, the music doesn’t grow or move that way.

Q: What changes have you seen in the industry over the years?

A: For one thing, the medium we use to listen to music has changed. We used to make albums, now everybody puts out singles. We used to make CDs, and before that it was cassettes and vinyl. Now you can put it online, and it doesn’t cost money. Just creating and sharing.

Styles of music change all the time. Whatever’s popular, people try to emulate. It was more avant-garde in the ‘80s. I had a band come out here with children’s toys they found and they did an album with that.

Q: What do you think makes a good record?

A: Sonically, it has to be entertaining, and it has to affect you physically. They call it ear candy if it’s sonically fun to listen to. Then it has to reach you inside.

Q: What keeps you interested in this work?

A: People. It’s a people thing. It’s not just one person, you’re working as a team to create something. One of the most important things in the studio is communication – that’s what makes a band work, their ability to communicate and take criticism from each other. Good ears and communication are the keys to music production.

Q: Does Binary offer other services?

A: Binary means two, so we are an audio-visual production company. We’ve done quite a few documentaries over the years. I’ve won the Mayor’s Art Award twice for my films.

Q: What goals do you have for the future of Binary Recording Studio?

A: Doing more of what I do. I enjoy talking to people, sharing with people in a creative context. There’s nothing like it. It’s almost a spiritual thing, I don’t know how else to explain it. You’re sharing together to create something. Once you do that, it’s hard to do anything else. Maybe tax accountants get together, but it’s a different thing. That’s why I like film too, because it’s a group of people creating something. My dream has come true many times already. Working with a group of musicians that are able to create something amazing, that’s what I look forward to.

To read about Shut Up and Listen, a podcast recorded with Ridgley at Binary Recording Studio, click here.

Halley Buxton (she/her) is a city life reporter for The Front. She is in her final year at Western with a major in creative writing and a minor in journalism. In her spare time she loves reading, writing with friends and collecting CDs. You can contact her at halleybuxton.thefront@gmail.com.