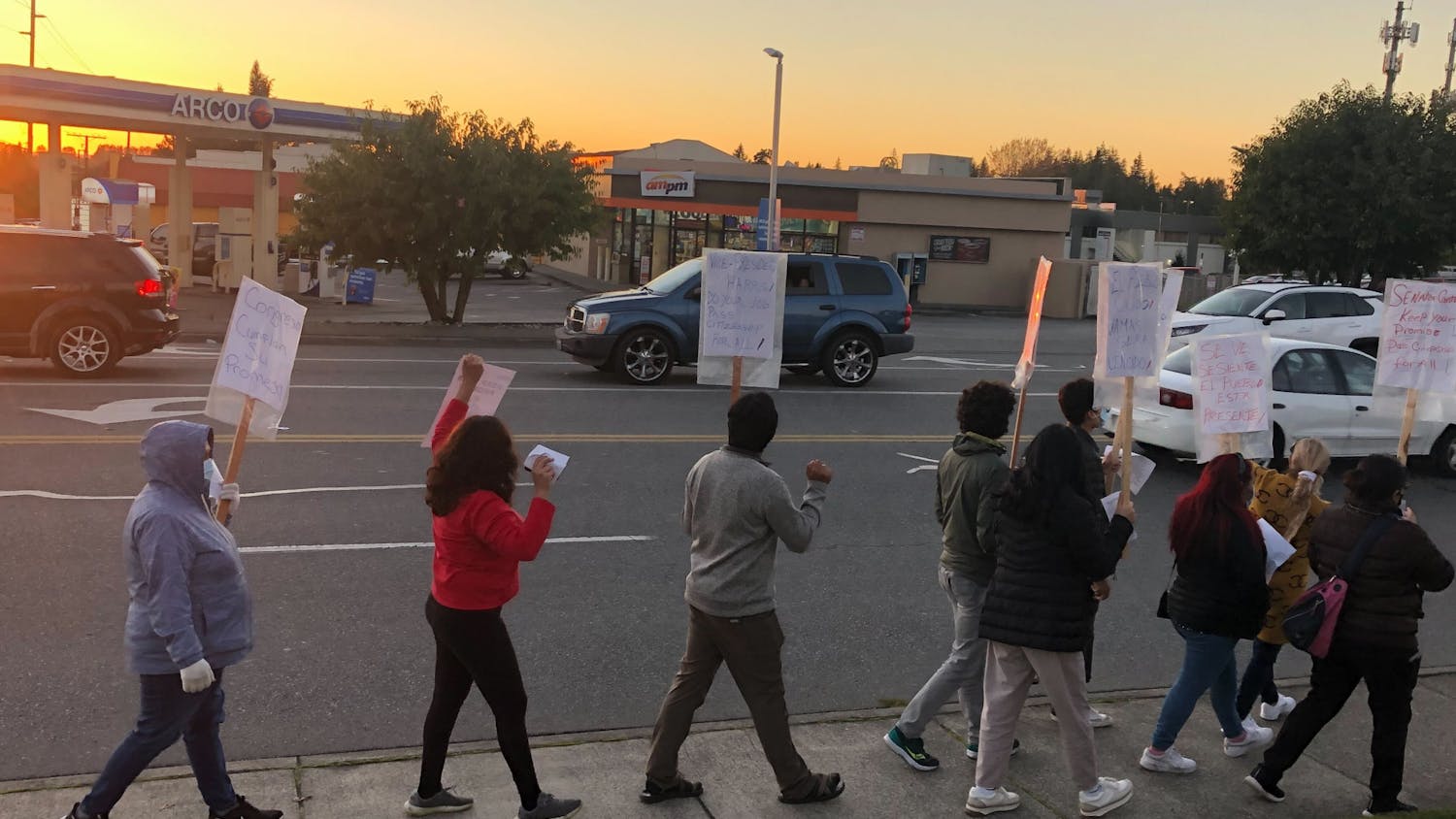

After discovering what they suspect is an unmarked ICE office in Ferndale at 1390 Commerce Place, protesters are gathering each week outside the industrial area harboring the nondescript building to voice their dissent for the immigration law enforcement agency’s secrecy and presence in the community.

Organizers Brenda Bentley and Liz Darrow, member of the Bellingham Immigration Advisory Board and legislative advocate for Community to Community Development, or C2C, host weekly vigils every Monday from noon to 1 p.m. on the corner of Admiral Way and Pacific Highway, alerting the public, demanding the facility be shut down and the 2019 facility expansion permits for new bathroom facilities be revoked.

Suspicion of the facility’s affiliation with ICE and the Department of Homeland Security reached members of C2C, a Bellingham immigrant and farmworker rights group, after August 2018 when an undocumented worker was detained at an office in Ferndale and again this summer when three more undocumented individuals reported being held at 1390 Commerce Place.

The tenants of 1390 Commerce Place were awarded a 20-year lease on June 12, 2018 and first occupied the building on Dec. 1, 2020 when the permit was finalized.

After neighboring businesses confirmed that 1390 Commerce Place was indeed an ICE office, hearing the news through word of mouth, C2C immediately began hosting their vigils, Darrow said.

The building sits amid Pacific Industrial Park and is completely unmarked, one reason for the protesters’ uproar.

“The only thing that would give you any indication that something was going on there is that it's completely surrounded by gates and barbed wire,” Bentley said.

Public Affairs for DHS-ICE in Seattle declined an interview about this Ferndale location, offering a list of ICE detention facilities instead. The building at 1390 Commerce Place was not among them.

Riley Sweeney, communications officer for the city of Ferndale said he could not comment on the facility’s operations.

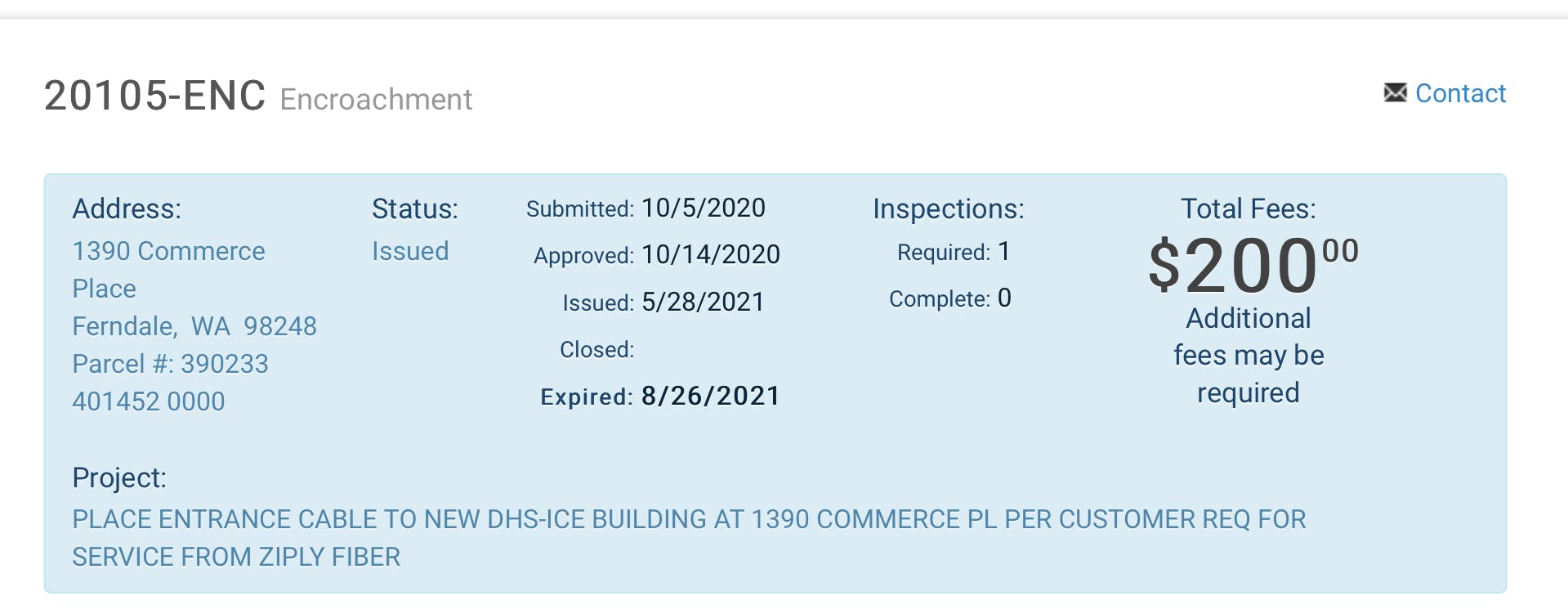

However, in a recent encroachment permitting fee issued on May 28, the city of Ferndale confirmed the project was for the “new DHS-ICE building at 1390 Commerce Place.”

Through their own research, organizers discovered that the building was leased to ICE by Mahmoud Boulos, the owner of 1390 Commerce Place and founder of SYB Holding Co., and that Boulos earned nearly $2 million off the contract.

On a catalyst submittal for the proposed Boulos Twins buildings on 2130 Main St. in Ferndale, background information about Boulos accredited him with bringing a number of industries to Pacific Industrial Park, including ICE.

Boulos, along with his office, declined an interview with The Front and would not confirm the identity of the agency occupying 1390 Commerce Place for fear that they would get in trouble with the tenants.

On the June 2018 lease award, the document lists the building space type as “Office, Warehouse, Law Enforcement.”

Vigil organizers also learned the office was approved for a facility expansion permit in November 2019 that included 13 new lavatories and two shower stalls.

“It's clear that the purpose of the office is to detain people because they've made these upgrades to it,” Darrow said.

These facilities were installed as the city of Ferndale determined that 13 new lavatories and two showers would not have a dramatic impact on the city’s utility system, Sweeney said.

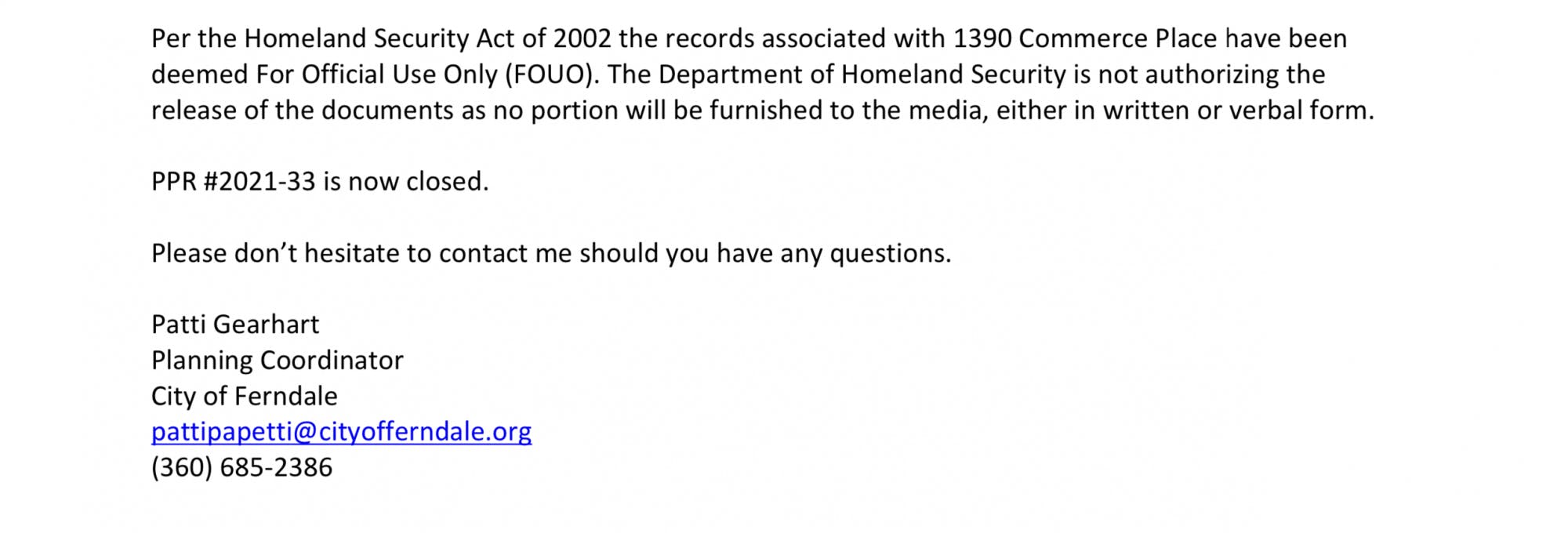

The Front submitted a public records request to the city of Ferndale for site plans and construction drawings for the building. The Department of Homeland Security responded to the public records request instead of the city, establishing that no portion of the requested documents may be released to the media.

Sweeney said the fact that protesters are unhappy with the office is not enough reason for the city to rescind the permit, as the fees have been paid and the legal requirements have been met.

But for community members present at the vigil, the suspected ICE office and its new facilities are more than just a contract. ICE has brought fear for the safety of their neighbors.

In a post from August, Dena Jensen, operator of the Noisy Waters Northwest blog, said “[They] are going out into the community and separating families by sending them off to detention centers and meanwhile, everything surrounding these offices has to do with keeping families together.”

Ralliers and organizers present at the vigils made the extent of their intentions clear while they protested.

“We are absolutely abolitionists in our goals,” Bentley said. “We don't believe that ICE can be reformed in any way and that it is a racist, inhumane and unnecessary agency.”

For some, the matter hits closer to home.

Vanessa Malapote, chair of the Latino Caucus for the Washington State Democrats, spent her 33rd anniversary of coming to the U.S. as an undocumented immigrant from Nicaragua at one of the vigils on Nov. 1. She crossed the border with her brother as unaccompanied minors without their parents.

“When it comes to illegal immigration and people being undocumented, there's so many different factors that play in,” Malapote said. “Because of [U.S.] military aggression [in Latin American countries] and because of the blockade, we had a lack of food. I remember being a little kid and having to make lines to get bread.”

Malapote is now a U.S. citizen and stands with fellow community members as they defend their undocumented neighbors outside 1390 Commerce Place and criticize the city and ICE’s lack of transparency surrounding the office.

“You would never know it was an ICE facility unless you specifically looked it up,” said Tina McKim, a member of the Birchwood Food Desert Fighters who was among the protesters.

Sweeney said there is no law in Ferndale requiring signage for businesses, only that signage not be obnoxiously large.

Protesters also scrutinized Boulos and ICE for never announcing the office publicly. For Sweeney, this lack of public disclosure was expected.

“It was not something that I got a press release about,” he said. “Border patrol doesn’t send out a lot of press releases.”

The city of Ferndale does not have an agreement with border patrol to have the office at 1390 Commerce Place, nor does it have any written agreements with border patrol, except for potential verbal mutual aid agreements, said Sweeney and Patti Papetti, planning and engineering support specialist for the city of Ferndale.

Protesters at the scene felt left in the dark about the office and wanted “to be involved and aware of the process before a detention center like this is embedded in the community,” Darrow said. “I think it would be easier to keep it from happening than to shut it down.”

Organizers at the vigil think there may be more ICE facilities in Whatcom County.

Activists have discovered similar unmarked ICE facilities in other cities that were once kept secret and protested them with vigor. In June, activists in Newark, New Jersey, discovered an undisclosed ICE office hidden behind the facade of a nondescript building, drawing protesters to their doorstep. A similar office was found in Fresno, California, in 2018.

Neither offices were listed on the ICE list of detention facilities, but both were specified as transportation centers for detainees being processed for long-term detention at other facilities.

Public Affairs for ICE-DHS in Seattle would not clarify if the 1390 office was used for detainee transportation either.

Locally, Darrow said she would look at other permitting processes to figure out how the community itself can stop more offices from being established, because many community members feel unsupported by their local government.

“When you see an organization terrorizing your neighbors, your community members, people who live next door to you, you stop that,” McKim said.

“I would consider it fortunate that you know the property owner, because he is also responsible for bringing this into the community and profiting off of it,” Jensen said, urging protesters to call and voice their dissent at Boulos’ suspected business with ICE.

Community members can join the vigils every Monday from noon to 1 p.m. at the corner of Admiral Way and Pacific Highway and find more information at the C2C Dignity Vigils and Actions Facebook page.

“The more people we have talking about it, the less secrecy that ICE has,” McKim said. “They really thrive on secrecy, and that's what allows them to keep operating and keep stealing our friends and neighbors.”

Kai is a senior at Western and has decided to finish his undergrad journey with News/Editorial Journalism. His focus is on social issues and is committed to the people within these stories.