This piece was written for Western's advanced reporting class, and was submitted to The Front for editing and publication.

Content Warning: This article contains language that may be triggering or traumatizing to some readers. CW: Sexual violence and suicide

By Lauren Gallup, Makenna Marks and Payton Gift

Sitting at their laptop, a Western Washington University student goes through the first module in the program entitled, “Sexual [Assault] Prevention Ongoing: Taking Action.” They move from page to page, exploring what the course contains, with definitions of sexual misconduct, a pre-course quiz and pages titled “Recognizing the Problem,” and “Microaggressions.”

Clicking through the pages is as simple as scrolling to the bottom and finding the “next” button.

After four modules like this and a post-course survey, the course is complete. The student has satisfied Western’s mandatory sexual assault prevention training requirement.

The course is offered through the company EverFi, and it's been mandatory at Western since 2015. In fall 2020, Western began requiring students to complete three years of training.

But beyond satisfying a requirement, what does the online training do?

Researchers, and evidence at other universities, show that online training, and specifically EverFi’s program, are ineffective at changing attitudes and beliefs about sexual violence.

“When your university only does these short term, quick online programs, it sends the message that they don't care about sexual violence. It sends the message that they're not taking it very seriously,” said Nicole Bedera, a sociology doctoral candidate at the University of Michigan who studies sexual violence on college campuses.

Beyond being ineffective, the training can also be harmful. Research has shown ineffective sexual harassment training can increase incidents of harassment in the work place. This can be traumatizing to survivors, Bedera said.

Students can opt out of the training if they fear it would be traumatizing. One to two percent do, said Jessica Dean, Western’s sexual violence prevention training and outreach programs specialist. That percentage doesn’t begin to encapsulate the total number of those who will experience sexual violence in college. According to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network campus sexual violence statistics, 13% of all college students will experience sexual violence while in college.

Many colleges, including Western, turned to online prevention training as a means of uniform education for their campuses. The expectation of Western to provide this programming comes from the the 2013 Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act amendments to the Clery Act, which states that institutes of higher education must provide sexual assault prevention training to students and employees, according to the Know Your IX website.

In 2016, students surveyed at Western requested improvements in the training, including having in-person courses, which researchers say are more effective.

Western used to have an in-person prevention program that focused on men’s role in preventing sexual violence on campuses. As sexual violence is a gendered issue, with men constituting the majority of perpetrators, researchers say this focused prevention works. But the grant that began funding the program in 2000 wasn’t renewed after 2006.

This experience of Western students might be about to change — Western’s contract with EverFi is ending on June 30 and the university is in the process of reviewing proposals from vendors for sexual assault prevention programming. Yet the criteria for these proposals are still geared toward online training.

Eastern Washington University used to use EverFi’s program, but switched to an in-house prevention training, aiming for a more customized and applicable experience for Eastern students.

Why does Western continue to use ineffective prevention programs when the university has used more effective programming in the past?

Ineffectiveness of online training

The online format Western has chosen to adopt is common. The sexual assault prevention program formerly called Haven through EverFi is used at 1,300 institutions, according to a research study published in January 2020 in the “Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice.”

Bedera said these online trainings are often ineffective.

“One thing we know is that sexual assault, and our gender norms that allow sexual assault to take place, are so deeply ingrained in us, in our culture so that short, one time, or once a year kind of programs are not enough to intervene,” Bedera said.

When measuring efficacy for sexual assault prevention, the metrics are changes in attitudes and beliefs, not crime statistics, as reporting of sexual assault is influenced by other factors.

At Western, Dean recognizes the potential shortfalls from online training.

“We've all learned through this past year, online learning in general has some very different and specific needs around it,” Dean said. With this kind of training, Dean said it’s important to make sure the content is engaging and not presented in a format where users can quickly click through without retaining information.

Ultimately, Dean said online training lacks the accountability that would come with in-person training.

EverFi’s program now goes by SAP for sexual assault prevention, or simply EverFi, Dean said. Dean, who has been working at Western since 2019, said the change was made prior to her arrival but to her knowledge, did not make any major changes to the content.

SAP has been shown to be ineffective.

Charlene Senn, a professor in the department of psychology at the University of Windsor in Canada, said SAP is ineffective because it doesn't follow the principles of effective assault prevention. She explained that every external evaluation of the program has shown this.

In the January 2020 study, researchers Claire Kimberly and Alisha M. Hardman looked at the use of EverFi’s online Haven program at four universities. Kimberly and Hardman found there were not notable changes in students’ attitudes towards sexual violence after participating in the program.

The study was conducted at the four largest public universities in Mississippi with 661 students who had never participated in sexual assault prevention training. Before the training, students completed a survey measuring beliefs related to rape and coercion, on the 20-item Sexual Beliefs Scale, which contains five subscales. They then took the same survey after the training.

Measuring on a scale of 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), the researchers found little difference before and after the training.

The mean for the “token refusal” subscale, which measures the belief that if a woman appears interested in a man, he is allowed to force her to have sex, was 1.21 prior to the training and 1.17 after the training. Showing even less of a change, the mean for the “leading on justifies force” subscale, which measures the belief that women prefer forceful sexual interactions, was .39 before and .38 after.

There was also little change observed in students’ knowledge of legal questions, with the mean before the training being 6.25 and then after, 6.22, measuring on a scale of 0 for no knowledge to 7 for complete accuracy.

In the conclusion, the researchers stated, “While online modules are an efficient way to reach a large number of students, it is unlikely that a standalone, brief online prevention program will be able to significantly alter attitudes, knowledge, and behavior in ways that will ultimately reduce the occurrence of sexual assault on college campuses.”

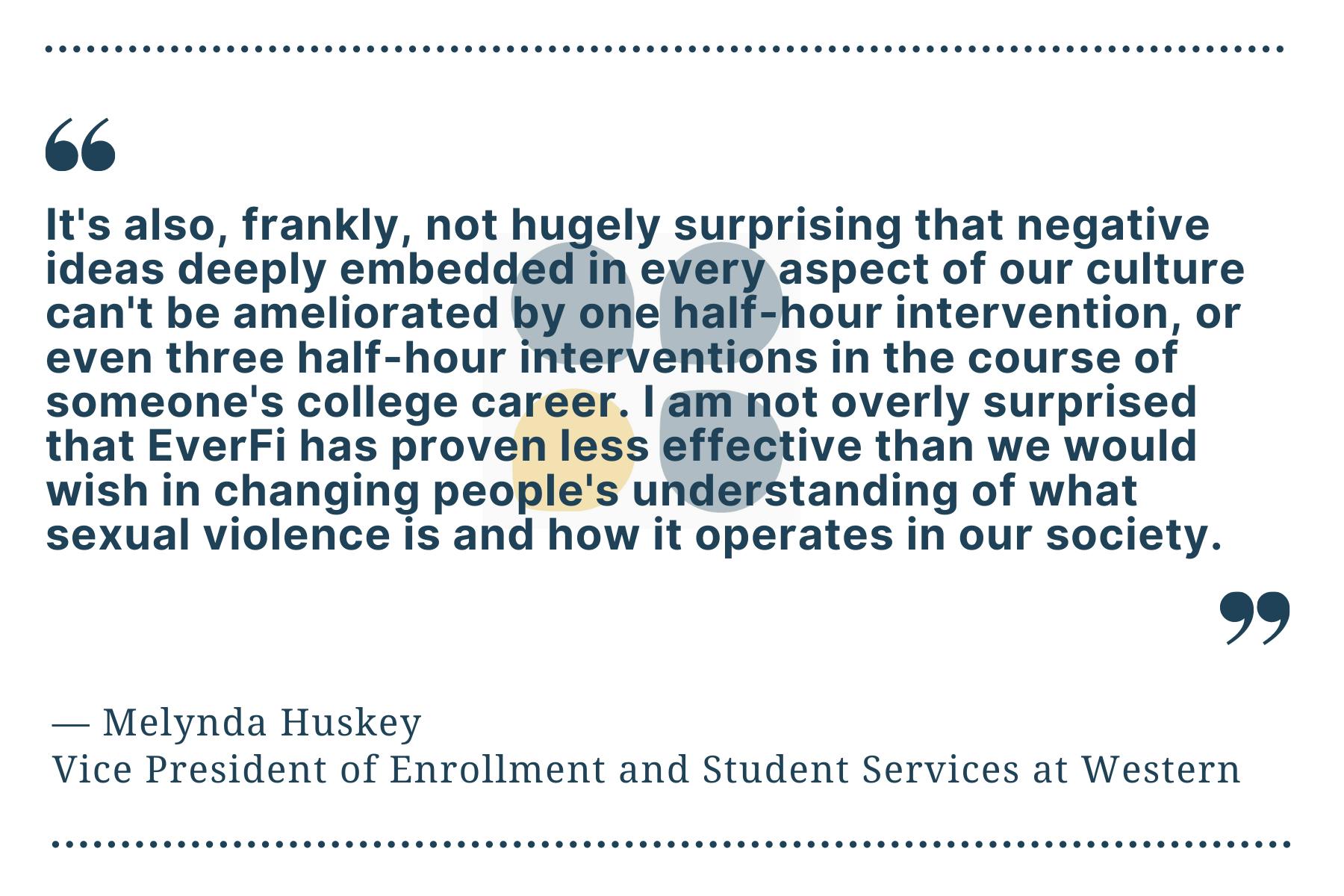

As it turns out, the lack of EverFi’s program’s effectiveness came as no surprise to Western. Melynda Huskey, vice president of Enrollment and Student Services, said she was aware of the 2020 study, as well as other recent studies on online prevention efficacy.

While Huskey was disappointed to learn about EverFi’s lack of effectiveness, she was not surprised that online prevention courses in general do not help or further educate students on sexual violence.

“It's also, frankly, not hugely surprising that negative ideas deeply embedded in every aspect of our culture can't be ameliorated by one half-hour intervention, or even three half-hour interventions in the course of someone's college career,” Huskey said. “I am not overly surprised that EverFi has proven less effective than we would wish in changing people's understanding of what sexual violence is and how it operates in our society.”

Despite the program’s lack of effectiveness, Huskey said in a follow-up email that other factors go into choosing large-scale training.

“When we plan for a large-scale training, and most especially with a training as vitally important as this one, we think about timing, about accessibility, about efficiency, about the resources available, including personnel, funding, space, and infrastructure for tracking compliance and managing follow up needed for the 8,000 [plus] students we train each year,” Huskey said in the email.

Senn, the psychology professor, said part of the reason that this training may be ineffective is the ability to click through the content. She also added that effective prevention should be gendered, as the issue of sexual violence is majorly a gendered issue.

Senn helped develop a program specifically focused on empowering women that has been shown to be effective. At the time she began this work in 2003, she said other programs were either ineffective or harmful, saying they sometimes increased men’s perpetration.

Training may be harmful

A training that results in no changes in students’ beliefs may be having a different impact on the campus community. Beyond being ineffective at creating change, the programming itself has the potential to be harmful to students, Bedera said.

“When your prevention is poor quality, we've talked about this before, but it does send the message that the university doesn't care,” Bedera said.

She said that in research on sexual harassment trainings, men exposed to poor trainings are more likely to commit acts of sexual harassment. While this research is on anti-harassment training in the workplace, Bedera said the trainings “are almost identical and they're on a very similar topic.”

“A lot of universities like to act as if doing something is better than nothing,” Bedera said. “But in fact, we're finding that doing the wrong thing is worse than doing nothing.”

While Bedera said there isn’t much research on whether sitting through sexual assault prevention training is retraumatizing to survivors, she said, “It's not a stretch to assume that it is. Survivors tell us that it is.”

When it comes to survivors of sexual violence, Huskey said the last thing Western wants to do is make things worse.

“Obviously we're deeply opposed to traumatizing survivors,” Huskey said. “I think that it should go without saying that we do provide an exemption for survivors.”

Huskey said it's important to understand the nuance of what harm can be done when there's global harm from an ineffective program that fails to prevent or respond adequately to sexual violence.

Deidre Evans, Western’s CASAS Survivor Advocacy Services Coordinator, said in an email she has heard from some students that the training can be traumatizing. Evans said if this is the case, exemptions are allowed, which Western supports. She also said she can offer support to students who have completed the training.

“I have heard from some survivors that they learned about available resources from the mandatory training and that is how they got connected with me for support,” Evans said.

In her role, Dean manages the logistical elements of running the SAP program. While her title is sexual violence prevention training and outreach programs specialist, she said she manages all EverFi training for Western students, including AlcoholEdu. This includes fielding questions students might have about the programs, assisting with technical issues and removing holds from students’ accounts.

Another part of Dean’s job is granting students exemptions from participating in the SAP course. Western students are currently required to take three years of the SAP training, according to Western’s website.

Students who have a history of sexual violence or assault can opt out of the course, and Dean said she feels this process is “pretty easily accessible.” In emails communicating to students that the training must be completed, Dean said information about opting out is included.

She acknowledged the potential difficulty of having to reach out to be given an exemption.

“When you are in a stressful situation, you see a term that triggers you like sexual assault, it can be hard to actually sit down and read that email,” Dean said. “And unfortunately there's not much we can do.”

Dean said when a student says they have a history of sexual violence or would struggle with the content, the exemption is given.

“We only grant exemptions for students who have a history of personal violence and feel uncomfortable taking the training,” she said.

While Dean said it is a rare occurrence, she said in her time at Western, she has received a handful of requests not specifying why they were making the request, in which case, she has had to send a follow-up email asking them to provide a reason.

One to two percent of students request an exemption for each time the program is required, Dean said. According to the student demographics on Western’s quick facts webpage, 16,142 students attend Western, meaning anywhere between 161 and 323 students are requesting an exemption.

She said once a student receives an exemption, they are not enrolled in future years of the training.

Bedera said campuses using poor training sends a message to survivors.

“For survivors, it feels like we don't value you,” Bedera said. “And so that's going to be inherently traumatizing.”

She said the problem isn’t talking about sexual violence, but again, how it is talked about.

“You can talk about sexual violence in a way that's liberating,” she said. “The problem isn't just saying, like all prevention is inherently bad for survivors. Nobody's saying that. What we're saying is the wrong type of prevention is going to be hurtful.

WWU used to provide in-person training

Western’s use of EverFi’s SAP program hasn’t been it’s only method of prevention.

In 1999, Western’s Director of Prevention and Wellness Services Pat Fabiano applied for and recieved a grant from the Department of Justice as part of the Violence Against Women Act. Written into the grant was the Men’s Violence Prevention Program, a component of Prevention and Wellness Services that would specifically focus on men, said Brian Pahl, the person who was hired to coordinate the program in 2000. Pahl ran the program until 2006, leaving after it became clear the grant would not be renewed.

As Pahl remembers, the grant amount was between $200,000 and $250,000, covering his program, salary and other programs and expenses, such as CASAS.

In a guide titled “Campus Sexual Assault Resource & Information Sharing Tool,” it states, “Given that 98% of sexual offenders are male, men have a special responsibility to prevent violence.” The guide was published in September 2002 for Washington state colleges and universities addressing sexual assault.

“Our effort was acknowledging that men are the primary perpetrators of sexual assault, dating violence, and therefore men should be involved in trying to stop the problem,” Pahl said.

Pahl’s responsibilities in the coordinator position included leading the now defunct student group, Men Against Violence, in doing education on campuses and in residence halls and running social marketing campaigns.

The guide also states the program is based on the belief that violence is preventable.

“This wasn't a program that was just about, ‘Let's create a presentation and go into a residence hall and deliver a presentation,’” Pahl said. “But also about rethinking manhood and masculinity, rethinking sexuality.”

Pahl’s interactions with students encompassed different roles as counselor, teacher and peer.

“It was really about attempting culture change,” Pahl said. “And when you do that, it's slow. It takes time.”

In group meetings, Pahl said they would process information from women in their lives about their experiences with sexual violence, as well as toxic masculinity and sexism. They would also discuss how to be an ally and have these conversations with the men in their lives.

Senn said the programs that are promising in terms of reducing prevention are focused on men.

The majority of men are non-coercive and don’t hold hostile attitudes towards women or support sexual violence, Senn said, so this kind of social norms education encourages non-coercive men to see that they are in the majority and stand up against sexual violence.

Part of Pahl’s work was recruiting students to be part of the lifestyle advisor program, which he said has now transitioned into Wellness Advocates. Those students took a class during spring quarter to prepare them to be peer health educators, Pahl said, and then they served in these roles for a year, doing things like presentations in residence halls, tabling and helping with social marketing campaigns.

Pahl said sometimes students were required to participate in educational sessions with him because of the decision of a judicial process.

From this work Pahl did, he said he couldn’t point to large-scale, cultural change, but instead that he recognized the difference in one-on-one interactions he had, where men discussed how to treat women respectfully, pushing against the narrative of sexual conquests and asking for help supporting the survivors in their lives.

Pahl said another big part of this work is not only preventing these acts, but being supportive of survivors.

Ultimately, Pahl said, “I knew we were making a difference in some people's lives.”

After Pahl left in 2006, a Western student stepped into his role, transitioning into full-time work. Pahl said he believes the AS added a fee to pay for the coordinator position, but as far as he knows, his replacement was only in the position for two years.

Under the “Emotional Wellness” category on Western's Prevention and Wellness Services website, there is a program called “Men's Resiliency.” According to the website, the program “aims to promote a positive and healthy collegiate experience for male-identified students.” The program also “challenges cultural male-normative expectations of masculinity, with the goal of creating a healthier campus environment for all.”

This program does not explicitly state the importance of men recognizing their role in perpetrating violence and ultimately being responsible for prevention.

“I think it's really sad that these kinds of things don't still exist,” Pahl said.

Pahl now works for Bellingham Public Schools as an instructional technology coach and hasn’t worked in the field of violence prevention for a while.

Speaking broadly, he said, “I think whether we're talking about this issue, or if we're talking about racism or homophobia, I think institutions need to take a really hard look at themselves and ask themselves, ‘What are they doing that contributes to systemic problems?’ and then work to make changes.”

And in terms of prevention programs, he said they shouldn’t be focused solely on providing information, as that alone won’t change people’s behaviors.

“[Prevention is] not just about information,” Pahl said. “It's about behaviors and attitudes. And the information alone isn't going to change people's behaviors. And so that seems really unfortunate if that's the direction things are headed.”

Pahl said if prevention is just presented through a computerized course, it’s missing this.

Students want something better

Jade Phillips is a Western student as well as the student coordinator for Planned Parenthood Generation, a club focused on advocating for equity, justice and education within the realms of sexual health.

As a student herself, Phillips has taken the EverFi prevention courses before, but recently reviewed them once again. This time around, Phillips reviewed the courses with more of a critical eye, and noticed a few things she didn’t catch before.

While she said it is important to continue having valuable conversations about sexual assault on college campuses, Phillips noticed that with the nature of online learning also comes with a lack of student engagement.

“I have heard from different students questioning whether the training is super helpful or effective in their own lives,” Phillips said. “I think that maybe there's a possibility or likelihood that students didn't really get all the information or engage very deeply with the information, just because of the nature of an online training.”

On the website for Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, the nation's largest anti-sexual violence organization, students and faculty can rate the EverFi program out of five total stars. The average rating from students was 2.8 stars. Three of the student ratings are credited to Western Washington University, all completed on October 11, 2018. Two of the ratings are for three stars and one for fours stars.

The first provides no comment, but the second stated, “It was kinda of too long, I remember a lot of my friends just skipping through it” and the third stated, “[I] thought it was pretty trivial or common sense. I wish it had been a bit deeper.”

Other students who completed ratings could either not be reached or didn’t respond to inquiries regarding their ratings.

Survey responses from the 2016 Campus Sexual Violence Prevention Task Force Final Report indicated Western students wanted more in-depth assault training. One hundred and fifty students suggested improving the current training, 23 of which recommended requiring a GUR course focused on sexual violence and the parameters of consent. Students also expressed the desire to have in-person training in addition to online courses.

“The mandated trainings are one element of a much larger network of prevention and response, which is overseen by highly-qualified professionals,” Huskey said, referencing Western’s Prevention and Wellness Services.

The same year Western began using EverFi’s online prevention training, Washington state took legislative action to attempt to combat sexual violence on college campuses. Senate Bill 5718, signed by the governor in May 2015, created a task force to focus on campus sexual violence prevention.

The task force released the 2016 report, evaluating sexual assault statistics at colleges, including Western.

Responses from the student survey given in the report showed that out of the students affected by sexual violence, only 8% of students harmed by sexual assault reported it to a Western employee. Reasons given by the survey for not reporting said thinking the incident was not serious enough to report, not wanting action taken and not needing any assistance. Sixty-one percent of students surveyed felt Western was doing a satisfactory job of investigating instances of assault.

Western began using EverFi’s online sexual assault prevention courses in 2015 after collaborating with the university’s Associated Students Executive Board. Shortly after the decision was made, the board voted to make this training mandatory for all Western students.

Annika Wolters was president of the board in 2015 and remembered that the vote to make the training mandatory was more of a technicality.

“I believe it was already mandatory, but [Western] just didn't have a written policy that it was mandatory,” Wolters said.

The board had a say in what program to choose as well. Wolters remembers narrowing the decision down to programs from two different companies before settling on EverFi.

“I remember that we weren't absolutely in love with either one of them, but we chose EverFi for representation reasons,” Wolters said. “I think it showed a little bit more diversity and I think it also had some helpful tips on bystander training.”

Out of the final two programs Wolters and the rest of the board had looked at, Wolters admits neither of them were going to check all the boxes.

“Some of these mass produced training sessions aren't perfect,” Wotlers said. “One of them had blue stick figures for people. ‘Why were we even looking at this?’ The other program was definitely not the one that we wanted.”

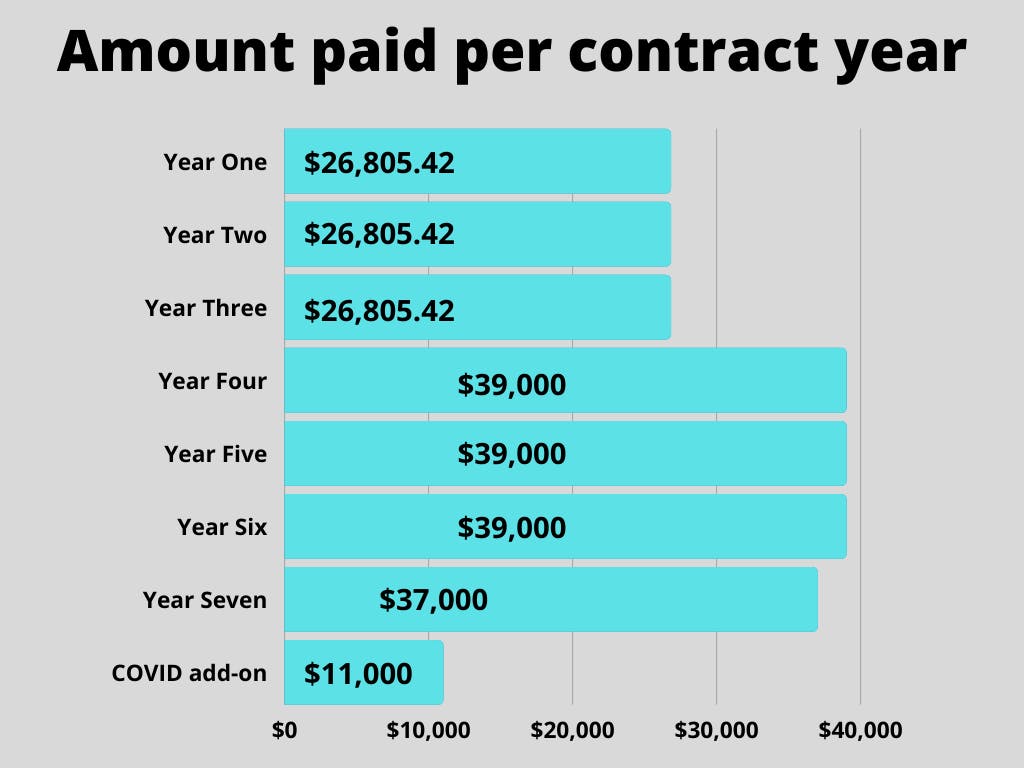

From public records obtained during reporting, Western has spent an accumulated $245,416 on EverFi since 2015.

Western began contracting with Everfi in 2015, at which point they entered a three-year contract, paying $26,805.42 yearly for both the AlcoholEdu and SAP program. A renewal for a second three-year contract was made in 2018, this time for $39,000 a year for the same programs.

This renewal was made in 2017, which explains why Western paid $65,805.42 to Everfi in 2017, as that would be the combined payment of $26,805.42 and $39,000. And this accounts for zero dollars paid in 2018.

In 2020, Western renewed the same contract with Everfi for the same amount for a year, which explains the $76,000 payment as $39,000 for those two years. In 2021, Western contracted with Everfi for an additional COVID-19 program, which cost the university $11,000.

What academics say makes for better prevention

Senn, the psychology professor at the University of Windsor in Canada, said click-through online programming is not the kind which leads to effective prevention, but universities use them because it makes administrators feel they are doing something for every student.

“One of the things about the practical aspects of prevention is that often administrators, particularly, want a single solution,” Senn said. “And we know that sexual violence is a very complex problem and that there is never going to be one program of any kind that is going to be effective and actually reduce sexual violence, perpetration and victimization.”

But, there are options that have proven to be effective and when used with other programs, can begin to prevent sexual violence and empower survivors.

Senn, based off the work of other researchers and with graduate students, created the Flip the Script with EAAA™ Sexual Assault Resistance Program. This program is specifically focused on helping women to unlearn cultural beliefs around sexual violence, understand the support systems they have and help to recognize potentially problematic or coercive relationships and interactions.

It is the responsibility of men, who are the majority of perpetrators of sexual violence, to stop sexual violence, Senn explained. This is why men’s violence prevention programs are promising in decreasing violence. But the program that Senn helped to develop supports women in understanding sexual violence is not their fault.

Senn’s program is for women, which made some people assume it was holding women responsible for sexual violence. But Senn’s intention, and outcomes of the program, show it is doing the opposite.

“Because there had been such terrible programming for women in the past that held women responsible, blamed them for what happened to them, it was critical to me that I could create a feminist program that did not reinforce women-blaming,” Senn said.

From the beginning of the program, Senn said it has reduced rape beliefs and myths and the blaming of women. It also has been shown to decrease self-blame in women who have been sexually assaulted after taking the program.

Senn said creating a targeted program is the only thing that works for sexual violence prevention.

“We know that if we just try and do the same thing for everybody, we're actually not being effective for anyone,” Senn said.

Since sexual violence is a gendered issue, the solutions must also be gendered.

Senn’s program is 12 hours total and while some people say this seems long, she said it’s a short amount of time to think, practice and apply new knowledge.

Bedera, the doctoral candidate who researches sexual violence on campuses, said in the college environment, successful sexual assault prevention programming should take a considerable amount of time to complete, suggesting training be closer to a semester.

Even with its effectiveness, Senn said her program shouldn’t be used on its own.

“We need a comprehensive sexual violence plan, that's always the case,” Senn said.

Senn said universities should use only effective programs. The programs for effectively reducing perpetration are still tenuous, Senn said, but in the meantime, she recommended schools also use bystander training, which aren’t effective in reducing perpetration or victimization but in improving bystander attitudes and behaviors.

Mandatory is also not the way to go for effective prevention, Senn said. She said making programs which require a deep level of reflection mandatory end up increasing resistance to them.

“The mandatory thing puts pressure on people for a lot of reasons, none of which is working to enhance the work of prevention,” Senn said. “You want people embracing it and moving towards prevention programming for positive reasons. Not because they're being made to”

Offering multiple options for students to choose from, such as bystander, men’s prevention, Senn’s EAAA program and other informational programs, could be a way to get all students what they individually need to increase prevention of sexual violence, Senn said, while satifying legislated requirements.

According to researchers in the study of EverFi’s Haven efficacy, “An online prevention program should be only one piece of a larger effort to prevent sexual assaults on college campuses.”

The researchers stated in their conclusion that “implementing complementary activities such as small group discussions, lectures, policy changes, and awareness or social norms campaigns that reinforce the messaging of the program is more likely to be effective in reducing sexual assaults on college campuses.”

Online prevention programs are not only common but mandatory, said Samantha Armstrong, vice president of student life at Eastern Washington University. She said online prevention courses are a response to legislation that requires public universities to give uniform and mandatory education regarding sexual assault.

EverFi’s SAP training isn’t the only method of prevention on college campuses, and neither are online trainings.

“We know from research that a lot of the education methods that are best are, in-person or in small group settings,” Armstrong said.

Legislation, though crucial, can limit how universities choose to educate their students about prevention, Armstrong said. Additionally, implementing online training modules comes at a cost.

“There is a price point to online training that can be extreme depending on the size of your institution,” Armstrong said. “It will not cost as much as staffing a full-time person to do this work, but depending on your organization it can cost anywhere from $25,000-$100,000 a year for a software platform.”

Eastern no longer uses EverFi for its online sexual assault prevention training. This came out of the desire to have courses made in-house and more specific to their campus, as well as financial pressure, according to Armstrong.

“We feel good about the fact that we were able to customize in a way that really speaks to the campus, what we have available for support, and what our expectations are,” Armstrong said. “It’s really about what is most engaging for students.”

Though Armstrong does think that online training is helpful, she said it should not be the only thing a campus is doing but instead a starting point for education and support.

“Campuses like Eastern, we do a lot of additional programming and messaging throughout campus,” Armstrong said. “Online training is a good start but it should really be a baseline for other work to be done.”

Armstrong said that while the online training is heavily encouraged, there is an option to opt out of the course when you begin the training, in case any students have a traumatic history with sexual violence that could make the topics of the training difficult.

However Armstrong does recommend Eastern’s training for survivors, or at least certain sections, so that they can be aware of the resources available to them on campus for both reporting and other support services.

Armstrong said that while online training is valuable, it can often be reduced to just “checking a box,” and that it is imperative that universities strive to do more to prevent violence on their campuses.

Potential for change

By the end of June, Western will decide whether to renew its contract with EverFi.

While Huskey is leaving the specifics up to Prevention and Wellness specialists, she said there “absolutely could be a change” in regards to EverFi and Western’s sexual assault prevention courses.

“Is there a better fit for us?” Huskey said. “There are some real advantages to online programs in terms of ease of delivery, follow up and personnel, but, in-depth, small group trainer-led programs also have a lot to recommend in terms of efficacy … I would imagine that almost anything would be on the table.”

As the contract with EverFi is set to expire, Dean said Western is soliciting proposals from different vendors.

“We're in the process right now of figuring out if EverFi is still the best fit for our institution, or if there's another vendor that would better suit the needs of Western students and employees,” Dean said.

Citing the ongoing procurement process, Dean wouldn’t comment on specific changes she would make to the EverFi program, saying she didn’t want to appear as favoring one vendor over another.

Phillips noticed that aside from only using English subtitles and primarily lighter-skinned models throughout the modules, she also noticed there was no representation of fat people or people with visible disabilities.

Looking forward, Phillips hopes that students will have more of a say in their prevention training.

“I would love to see Western open up the conversation and include students in this conversation about prevention,” Phillips said.

Dean said they take into account students’ responses to the surveys completed before and after the SAP training, where students have the opportunity to provide feedback.

An internal team, including Dean, will look at the proposals and evaluate them based on certain criteria. This criteria can be viewed in the Request for Proposals, which was posted on Washington's Electronic Business Solutions website.

In the RFP, it states that proposals were due May 24 at 3 p.m. The team finished evaluating proposals on June 7 and is now in the process of conducting interviews with proposers until June 15. The contract will then be reviewed until the award announcement is made on June 30.

Among the many questions asked of submitters in the RFP, was “Do you provide sexual assault prevention training focused on concerns of specific student populations (international students, non-traditional students, etc.?”

Whatever decision Western makes for the contract this June, it will be an important one.

“[Sexual violence] is a life-threatening type of violence,” Bedera said. “Women are murdered in the course of sexual violence and then [die] from suicide afterwards of dealing with traumatic symptoms as well. We're talking about something so serious where the suffering is so clear and universities can't find money for it. It's emblematic of the systemic devaluation of women on campus.”

If you or someone you know has been affected by sexual assault, domestic or dating violence, there are resources for you. All services by agencies listed below are free of charge.

CASAS: 360-650-3700

DVSAS 24-hour helpline: 360-715-1563

Lummi Victims of Crime 24-hour helpline: 360-312-2015

Lauren Gallup (she/her) is the spring 2021 managing editor of The Front. She is a fourth-year news/editorial journalism major, whose writing has been featured in Klipsun, 425 and South Sound magazines. Her reporting seeks to answer, provoke and increase understanding. You can find her retweeting great journalism @thelaurengallup or reach her at laurengallup.westernfront@gmail.com.