Push for name’s removal prompts questions about diversity, representation in Western’s College of the Environment

Western Washington University’s Huxley College of the Environment could be getting a new name.

Growing efforts by students and faculty to change the name of the College of the Environment highlight questions about the values of the Western community. These efforts come in response to recent research into the namesake’s contributions to scientific racism.

Sargun Handa, Western senate pro-tempore, said the idea of a name change first came on her radar last winter, during her term as a student senator. It was not until Western’s Black Student Organization included the name change in a list of demands published in June 2020, however, that the issue became a priority.

Fourth-year anthropology student and VP of Sustainability Zarea Lavalais was one of the students to sign the list of demands. She said she sees the renaming of the College of the Environment as an important step toward meeting the needs of the Western BIPOC community.

“[The Huxley name] really speaks loudly of how Western Washington University feels toward the most marginalized people in their community,” Lavalais said.

Francis Neff and Laura Wagner, College of the Environment student senators, have made the name change their focus this year.

Neff said much of the initial momentum toward a name change came from grassroots efforts. Neff and Wagner are two students among many others who have dropped the name “Huxley” and simply say “the college of the environment.”

On Jan. 25, both senators hosted a public forum for students to learn more and share their thoughts, where the role of a legacy review task force was discussed.

Handa said two students by the names of Laura Wagner and Kaylan Rocamora have been appointed to sit alongside faculty and administration on a legacy review task force. The task force is charged with reviewing the names of buildings on campus and of the College of the Environment. They have until May 31 to recommend whether the university remove any existing names.

“We really want the task force to value community input above all else,” Wagner said.

Lillian Propst, a third-year environmental policy student, echoed that desire.

“This is a name change that will represent students in the past and the future, and I think it needs to take into consideration community voices and what normal students like me have to say,” Propst said.

One concern Handa has is only two of the nine members of the task force are students.

Handa and Wagner said they hope to send out surveys and host additional forums to get lots of student input. An initial survey can be found here.

Western faculty have also shown support for removing the Huxley name.

Gene Myers, professor of environmental studies, said faculty from the environmental studies department signed a letter in favor of the name’s removal earlier this year.

Myers said College of the Environment faculty have been putting significant efforts toward diversifying the environmental field. Keeping a name that alienates students, he said, doesn’t fit with that vision.

“Those are blockages to getting us a more diverse set of people and perspectives represented in our field and in our college,” Myers said. “So we stand to benefit by removing this obstacle.”

Representation is a motivating factor in students’ action.

“[Huxley] is the college where my BIPOC friends feel the most unwelcome and unsafe. And that could be in part due to the culture that’s reinforced and enabled by that name,” Handa said. “How do we expect BIPOC students to enter that space when it’s not even made for them or welcoming them?”

Probst felt similarly.

“Environmental studies and science have a lot of obstacles to overcome regarding curriculum and policy and representation of BIPOC,” Probst said. “There needs to be a lot more work done by professors and faculty in making more room for people of color and communities of color in our curriculum specifically.”

Conversations about the Huxley name prompt big questions about how to reconcile the scientific field’s racist past with its current reality.

One starting point is examining that past.

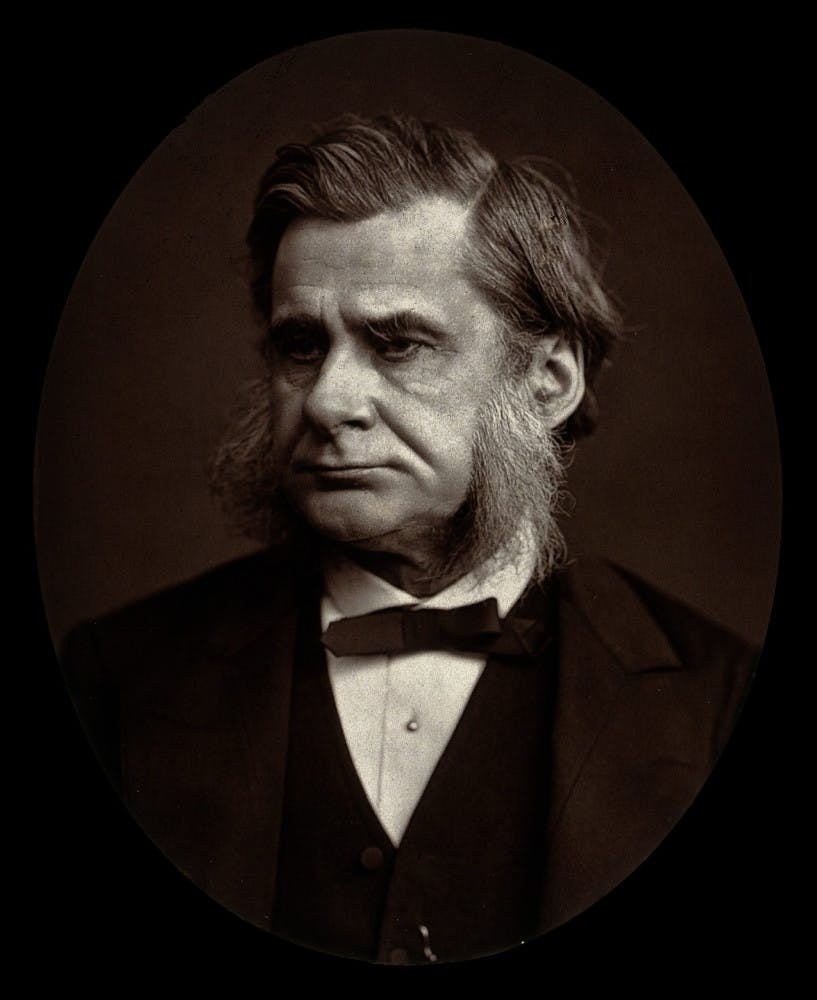

Nicolaas Rupke, professor of history at Washington and Lee University, has researched Huxley’s contributions to scientific racism.

Rupke said he defines this contribution as “developing a theory of human origins that requires racist ranking — taxonomic ranking from low, close to animals, and then to high.”

According to Rupke’s studies, Huxley believed the peoples he deemed as “lower”— such as Aboriginal Australians — were closer in similarity to apes than they were to Europeans, who he deemed as “higher.”

A specific essay Huxley wrote was problematic for many students: “Emancipation: Black and White.” In this essay, Huxley states his belief that the average Black individual is inferior to the average white individual.

Jon Marks, professor of anthropology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, said much of Huxley’s work didn’t pertain to race. In fact, Marks considers him a personal intellectual hero.

Marks acknowledged, when it comes to race, Huxley is not without blame. Despite being an abolitionist, he did not believe Black and white people were equal.

“His agenda was professionalizing science and science education,” Marks said. “And as long as you were on his team with that, he didn’t care if you were a racist.”

Despite Huxley’s contributions to scientific racism, some support keeping the name.

Myers said some people are worried a name change would alienate alumni or cause confusion. Others may think Huxley’s contributions to scientific racism are outweighed by his contributions to science, women’s rights and education, Myers said.

“These are moral questions that are very tricky to deal with. How good of a person in retrospect do we want the people we honor to have been?” Marks said. “I think we can’t judge scientists just in terms of what they discovered, because they are complete people when they’re doing the work.”

Andrew Billings, Ronald Reagan chair of broadcasting at the University of Alabama and director of the Alabama Program in sports communication, has studied mascot controversies in sports. He said when it comes to naming changes, the backlash is often informed disproportionately by tradition.

“Very little changes, but it’s the threat of change that’s very scary to some people,” Billings said.

Wagner said she and Neff find it important to advocate not only for the removal of the Huxley name but for its replacement. The search for a new name brings about more questions.

“To me, the real question becomes ‘Is there a story to be told and is it a positive or negative story?’” Billings said. “Is there a teachable moment there?”

Wagner and Neff’s vision is that the College of the Environment is named after a figure that represents a more diverse range of students.

“Really the cornerstone for all of this should be environmental justice,” Neff said.

Officially removing and replacing the College of the Environment’s name will take time. It will likely still be in progress when Neff and Wagner finish their term this spring. But many, like Handa, find hope in the momentum the senators, students and faculty have created.

“The good thing is that we have people who aren’t going to back down or quit,” Handa said. “We’re going to see this through.”