At Western Washington University, the desk of the director of the office of the internal auditor is unoccupied — but unlike the other desks and chairs on campus left alone since COVID-19, it has been empty since November 2019.

Its last occupant, auditor Antonia Allen, was fired that fall. A little over a year later, she filed a lawsuit for wrongful termination in December 2020, alleging she was fired in retaliation for revealing “ghost courses” at Woodring College.

Allen’s predecessor, Matt Babick, had settled the largest employment settlement in Western’s history just a month prior to her termination. Babick claimed he was pushed out of his role after attempting to conduct an audit related to the university's former President Bruce Shepard.

The investigation

Allen initiated the investigation into what some call “ghost” or “paper” courses in January 2019, after then-registrar David Brunnemer raised concerns with then-auditor Paul Schronen. Brunnemer was concerned the elementary education department was issuing internship credits for students who had not actually performed internships, according to a memorandum dated July 12, 2019, sent from Allen to Brent Carbajal, vice president of academic affairs, and Melynda Huskey, vice president of enrollment and student services.

On May 15, 2019, an initial draft of the investigation was given to Western administration, according to the complaint filed on behalf of Allen. Six days later, Assistant Attorney General Melissa Nelson drafted a memorandum, “for the purpose of dissuading Ms. Allen from contacting the [U.S. Department of Education’s Office of the Inspector General] (USDOE/OIG) about the Woodring Internship Ghost Courses Irregularities Investigation,” according to the complaint.

Allen responded that “she would not change the report to be consistent with Ms. Nelson’s advice and that in addition to reporting the resulting losses to the USDOE/OIG she would also be reporting losses to the State Auditor’s Office,” according to the complaint.

In communication with USDOE/OIG’s Western Regional Office Special Agent in Charge Adam Shanedling, Shanedling told Allen she was investigating fraud that needed to be reported to federal investigators.

The investigation concluded in June 2019. The final report, sent in July, found there may have been fraudulent courses at the Woodring College of Education.

Nelson’s office directed The Front to Western’s administration for comment.

The university said there had been no “ghost courses” offered. Paul Cocke, director of the office of university communications, defined a “ghost course” as “a class that exists only on paper, requires no academic course work from students and is provided to bolster the grade point averages and academic progress of selected students.”

Instead, Cocke said, via email, “the department enrolled fewer than 25 students in existing internship courses over the course of a few years, which allowed them to earn credits, even if they completed the requirements for the course during a different quarter. It is important to note that those students completed the appropriate amount of work for the credits awarded.”

“Western strongly disagrees that faculty and staff knowingly engaged in fraud,” Cocke said. “The University believes the intention was not to circumvent policies, but rather to help these few students who were struggling to manage tuition costs and complete their coursework. This is a legally complex issue.”

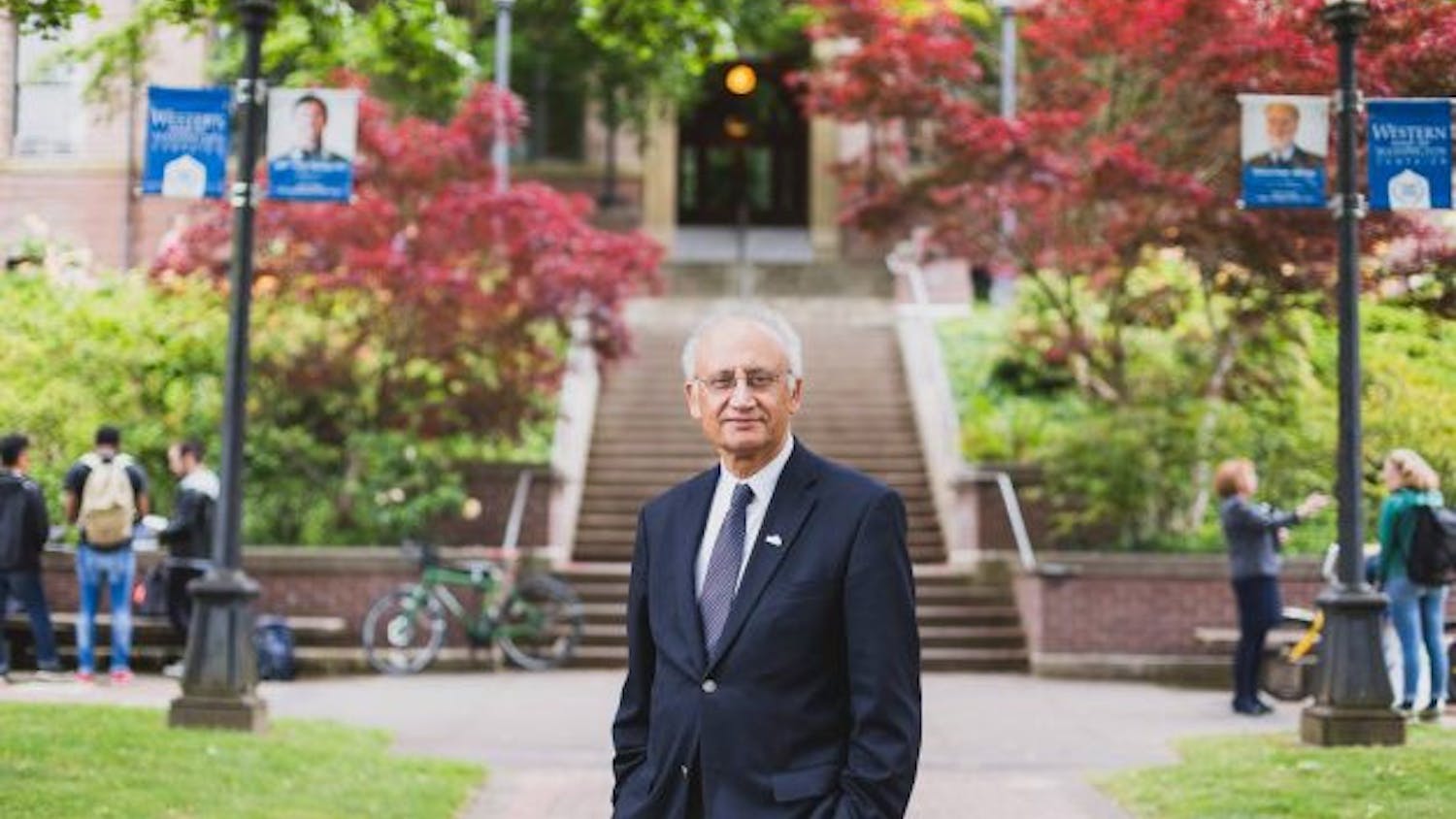

On Oct. 21, 2019, the same day Whatcom County Superior Court settled Babick’s case, university President Sabah Randhawa requested an Oct. 24 meeting with Allen, at which she was fired, eventually leading to the auditor’s suit for wrongful termination.

Addressing the university’s response to the investigation, Allen’s attorney, Jack Sheridan said, “The danger is if you take no action to try to cover it up, it could jeopardize your ability as a university to get funding for your students.”

The former employee

Allen came to Western in January 2017, hired as the director of the Office of the Internal Auditor, according to her complaint for damages, injunctive and declaratory relief. When she started, she had no concerns anyone would try to prevent her from doing her job, Sheridan said.

As an independent entity from Western, the Office of the Internal Auditor reports to the Finance, Audit, and Enterprise Risk Management Committee, as stated in the complaint. The committee consists of three trustees selected by Western’s Board of Trustees.

Sheridan said Allen, as a state employee, has protections under RCW 42.40, the whistleblower statute, after being terminated for reporting “improper government action.”

Western is a state institution. While the state auditor can investigate after receiving a report like Allen’s, they cannot offer any sort of remedy to wrongful retaliation claims, Sheridan said.

Adam Wilson, who works in state auditor Pat McCarthy’s office as the office’s external communications and legislative relations officer, said it has not investigated the specific case at Western.

But, Wilson said, “we can say generally that we are always troubled by complaints regarding undue restriction of internal auditors doing their work. We routinely review their work when planning our own audits.”

The most common course of action for state whistleblowers to pursue is in superior courts, like in Whatcom County, where Allen’s case will be heard, Sheridan said.

In Washington, the burden is on the state to prove they fired a whistleblower for a legitimate reason, not retaliation, Sheridan said.

“Everybody loves you until you do your job, and they don’t want you to do it and you get fired,” Sheridan said.

The university

After Western alumna Asia Fields wrote an article for the Seattle Times describing events within the Office of the Internal Auditor, the university’s president sent an email to Western faculty.

In the email, sent Jan. 12, Randhawa stated the elementary education department “enrolled fewer than 25 students in existing internship courses over the course of a few years, which allowed them to earn credits, even if they completed the requirements for the course during a different quarter.”

Cocke clarified via email that the number of students was exactly 25.

Western has yet to hire a replacement for Allen, but Randhawa said in his email they are planning to begin the process, which has been delayed due to COVID-19. During this vacancy, the state auditor’s office cannot fill the role of internal auditor, Wilson said.

Allen is seeking reinstatement to her job at Western as part of the lawsuit.

“We don’t want good people chased out of good jobs by people who are discriminating, or in this case retaliating,” Sheridan said. “As a society, we want to put those very good people back where they were so that they can do the job that they were hired to do.”

Sheridan said Allen is resilient enough to go back.

Cocke reiterated how the pandemic has affected hiring, including, “position funding considerations, outreach/recruitment challenges, applicant hesitancy to apply due to the pandemic, lack of in-person interviews and travel restrictions.”

During the pandemic, Cocke said “there have been some positions filled at Western, which [required] an approved exception,” as state agencies are in a hiring freeze.

“We value risk management and independent internal control processes that an effective audit function provides,” Cocke said. “And to that end, we will soon initiate the process of hiring a full-time internal auditor through a nationwide search.”

Western is regularly examined by the state auditor’s office, Wilson said.

“[We] will take the concerns raised about the role of its internal auditors into account as we plan the next audit of the university,” Wilson said.

The litigation

Allen filed the lawsuit against Western in December 2020.

As of Jan. 28, Sheridan said they are in the discovery phase of litigation, where documents are collected in relation to the complaint.

The next steps are depositions, recorded interviews with witnesses under oath, and then, unless there is a settlement, a trial. Depositions of public officials are public record, Sheridan said.

When the trial occurs, Sheridan said, a jury will decide the case.

“People want accountability in these cases,” Sheridan said.

Either side can appeal if the jury does not decide in their favor, Sheridan said. But, he said, “I have found with the state that we usually make a pretty good case.”

Whatever the outcome of the litigation, the practices outlined in the Office of the Internal Auditor’s investigation ended in April 2019, Cocke said. In addition, Cocke said “Woodring College has undertaken a full review of academic policy and provided training on policies for all relevant faculty and staff. In addition, the University Registrar’s office and administrative staff of the college reviewed individual student records to ensure the accuracy of those records.”

Lauren Gallup (she/her) is the spring 2021 managing editor of The Front. She is a fourth-year news/editorial journalism major, whose writing has been featured in Klipsun, 425 and South Sound magazines. Her reporting seeks to answer, provoke and increase understanding. You can find her retweeting great journalism @thelaurengallup or reach her at laurengallup.westernfront@gmail.com.