Screenshots of the Viking View web cam of Red Square from Western's website. // GIF created by Erasmus Baxter

Erasmus BaxterAfter a man was reported in the women’s bathroom of a Kappa residence hall last fall, Annie Gordon met with resident advisers and community members concerned about their safety.

As the Associated Students vice president for student life, Gordon dealt with campus safety concerns. There were many concerns as campus and the surrounding area were besieged by a string of indecent exposures, voyeurism incidents and an on-campus groping attack. One solution multiple students approached Gordon about was installing security cameras around campus.

The idea of increasing the number of cameras on campus is nothing new. In 2004, two students whose cars were burgled under Nash Hall told the Front they wished cameras were installed to deter thefts.

A 2016 survey by Campus Safety Magazine found 74 percent of higher-education institutions surveyed either adopted or upgraded video surveillance technology. An additional 13 percent considered doing so in the next 3 years.

This increase is attributed in part to a decrease in cost: in 2004 Western’s assistant police chief told The Western Front that installing cameras under Nash Hall would cost $70,000 to $80,000 — now, a system with 16 IP cameras goes for under $9,000.

In spite of this proliferation, expanded cameras are unlikely to come to Western soon. In a series of interviews, administrators, student activists and a former Associated Students board member all expressed a deep skepticism about expanding surveillance capabilities at Western.

However, the quiet implementation of another technology with large surveillance implications emphasizes how complicated the balance between privacy and technology can be.

Red Square web camIt’s a sunny summer afternoon in Red Square. A steady trickle of people pass through as junior Tess Davis works on her biology homework. Wesley Tran, a recent Computer Science alum, quietly focuses on his laptop in the shade.

Unbeknownst to them, and many of the hundreds of people who assemble in Red Square, they are being watched. A webcam perched on the fifth floor of Bond Hall is constantly streaming images of Red Square to the internet.

Neither Tran nor Davis are too concerned by this, however.

“I’m not doing anything wacky,” Tran explains when he finds out.

Davis feels similarly, but she’s conflicted. On one hand, she thinks it’s good to have a camera there for security reasons, but on the other, she worries about the prevalence of surveillance.

“We don’t have a lot of privacy today,” she says.

While Western does have cameras installed in some labs to protect equipment, this camera doesn’t offer much in surveillance capability. It doesn’t store footage and only provides one zoomed-out view of Red Square.

The camera mainly serves as a way for parents to view campus and for staff to check on the weather, Max Bronsema, whose WebTech office currently houses and maintains the camera, said in an email. It’s consistently one of the most popular web pages at Western, according to Paul Cocke, director of communications and marketing.

ATUS Director John Farquhar believes the webcam was first installed around 2000 when the office housed Western’s data center. Besides a brief stint in Miller Hall, it has remained there since.

The camera in Red Square was upgraded to one with a slightly wider field of view this year, but it had nothing to do with surveillance, according to Bronsema. The camera would only work in legacy browsers, which few people use, so he paid for an upgrade out of his office’s budget.

Darin Rasmussen, Western’s police chief, won’t rule out that police might check the webcam in future, giving the example of a mass evacuation scenario, but he’s unequivocal that they haven’t used it to monitor Red Square in the past. A public records request for screen grabs of Red Square taken by University Police in the last year returns no results.

In the meantime, Davis continues her homework. The knowledge she is being watched doesn’t bother her too much. She doesn't plan on doing anything different in Red Square, she says -- with maybe a few exceptions.

“I wouldn’t scratch my butt or something,” she says. But on the other hand, “maybe that would be funny.”

Cameras at Western

Currently, surveillance cameras at Western are set up in labs to protect computers and other equipment. The cameras stream to University Police dispatch but are only checked if an equipment alarm is triggered, according to Darin Rasmussen, Western’s police chief and director of public safety .

The agenda from a subcommittee Rasmussen chaired last fall that considered what Western would do in a situation like Charlottesville shows they discussed a long-term need for cameras. From an emergency operations standpoint, cameras would allow them to access events and know what was going on in real time and to avoid needing a warrant or permission to view bystander video after the fact.

In an interview, Rasmussen said the conversation was just brainstorming. After a meeting of the larger committee on Sept. 20, cameras weren’t mentioned again in the agendas.

“There would have to be campus support. There would have to be student support, faculty and staff, and there just wasn't the time to to generate that, develop it, or even have the debate,” Rasmussen said. “So, we moved on to things that we thought we could move on.”

He pointed to Western’s culture of free speech as one of the reasons why there are no plans or discussions about adding cameras.

Director of Communications and Marketing Paul Cocke agrees but thinks Western shouldn’t shy away from discussions just because there isn’t interest in adding cameras.

“I think Western's culture is one that is very wary of the whole concept of heavy surveillance,” Cocke said. “Now, we have the benefit of not being in a major metropolitan area. If we were Columbia University in downtown New York, I bet we’d have a whole different perspective on all of this.”

Rasmussen agrees with this assessment of the campus culture.

“It's really important when you're working on safety not to get too far out in one direction from the community you serve,” he said. “...we want to make sure that we're providing the level of safety and security that they're expecting with the resources we've been given, inline with best practices and industry standards. There's a lot of variability in there, and so what is the Western culture and the Western approach going to be in that variability?”

Gordon received the same reaction when she discussed the idea of cameras with other administrators. Director of University Residences Leonard Jones previously worked at universities with comprehensive surveillance systems in their dorms. However, when Gordon spoke with him, they shared concerns about how cameras could increase policing and surveillance in a way much of the community is opposed to. Administrators didn’t want to get involved unless they were sure there was student support. To gauge how students were feeling, Gordon partnered with the Residence Hall Association to distribute a campus safety survey.

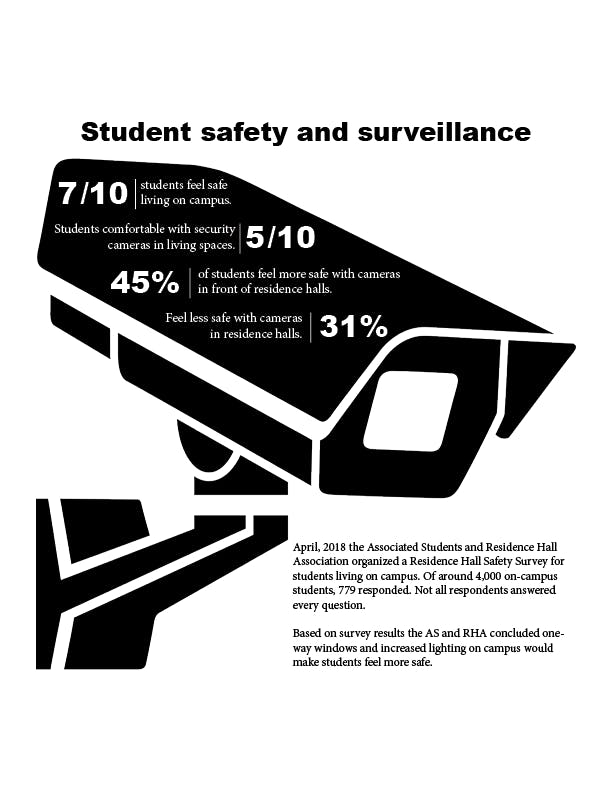

Seven hundred seventy-nine of the around 4,000 students living on campus filled out the survey. Not all respondents answered every question, but students rated the average feeling of safety living on campus seven out of 10. Comfort with security cameras living areas averaged five out of 10. Around 45 percent said security cameras at the entrance to residence halls would make them feel more safe, and around 31 percent said they would feel less safe or didn’t like the idea.

“Based off that, I don’t think it’s really likely to happen,” Gordon said. Instead, she thinks it’s important to focus on safety measures, like better lighting, that don’t come with as many concerns about privacy.

“Cameras aren’t getting at the roots of violence,” she said.

Safety for Whom?

When Samia, a WWU Students for Palestinian Equal Rights (SUPER) steering committee member, heard University Police discussed expanding security cameras, her first reaction was to shake her head in disbelief. (Samia asked to only be identified by her first name due to past harassment.)

“As a predominantly Arab and Muslim student group who grew up after 9/11, we are no strangers to government surveillance and the horrible impacts it had on our community,” she said. “I think the way that surveillance has damaged a lot of our communities is a testament to why that shouldn’t go forward.”

In a joint interview, Samia, Nadya Sharif, another SUPER steering committee member and Kate Rayner Fried, a SUPER member and Jewish Voices for Peace organizer, all described issues they had with surveillance at Western.

All see potential increases in surveillance as part of a larger picture of police surveillance of communities and activists of color. The way their Red Square display was handled last spring only serves to reinforce their concerns.

Timed to commemorate Nakba, the mass expulsion of Palestinians from what is now Israel, the week-long display featured a table to distribute literature and a mock wall. The wall symbolized the walls around Palestine and on the U.S.-Mexico border. Peacekeepers were also present, trained to defuse any potential trouble.

The Thursday before the display, administrators told SUPER that police and administrators would be coming to check on the event. SUPER requested they announce their presence and any police be unarmed or not in uniform — something Samia said administrators agreed to.

“We felt that police, especially armed police, would really escalate any situation, and we were really uncomfortable with that,” Samia said. “Also, a lot of the students organizing [the display] were students of color, students whose communities have really difficult relationships with police, and so we wanted to make sure we were all safe while we were out there just trying to educate people.”

Despite this, on Wednesday, three armed and uniformed police officers came by the display without announcing themselves and hung around the wall.

“The fact that the police decided to show was really frustrating and annoying, especially when we specifically said we don't want this to happen because we’re not doing a demonstration. This is just an educational thing we’re trying to spread awareness about,” Sharif said.

Rasmussen has limited knowledge of what happened that week because he was out of state, but he said he was never informed of a request to not have police present. If he had, he would consider it in light of what he thought campus safety required.

“The overall approach that I have on events, demonstrations, protests — all of those kinds of things — is to provide a safe and secure space for people to exercise their freedom of expression,” he said “This is no different, and a request to have or not have police presence is really going to be met with my overall assessment of what I think the safety and security of the campus needs.”

SUPER’s other issue was the constant presence of administrators at the event. Very few announced their presence as SUPER was assured they would, Samia said. Instead, they stood 10 feet from the wall and watched them. They all wore name tags, but they were hard to see unless you were looking for them.

What warranted such a large monitoring presence?

Rasmussen said his biggest concern was the side of the border wall prop about the U.S.-Mexico border. He felt it might draw off-campus protesters who might damage the display, so he considered the situation different than someone at a table distributing flyers. In general, he tries to allow Student Life to handle any issues, only involving officers if people’s safety or property are in danger. Even if there are disagreements or flare ups between groups, they’ll allow it to occur before getting involved, Cocke said.

However, SUPER members are skeptical. Rayner Fried attributed the presence to concerns about allegations of antisemitism and wanting to shut down conversations before anyone could make that allegation.

“I also think there’s a big racial element to this,” Samia said. “You see police presence at MEChA’s lowrider show, but you don’t see police presence when there are student groups led by predominately white students doing events in Red Square.”

The same racial element undercuts her concerns about police surveillance.

“I think that is a really ridiculous proposal to expand surveillance of students in hopes it will make certain people feel safe,” Samia said. “I don’t feel more safe when I’m being surveilled.”

Chilling Effect

Studies confirm people act differently when they know they’re being watched.

A 2016 study published in the Berkeley Technology Law journal found a dramatic decrease in traffic to Wikipedia pages related to terrorist groups directly after Edward Snowden’s revelation of NSA surveillance of internet traffic.

Due to such differences in behavior, theorists argued privacy is essential for individual dignity, identity and even intimacy. The authors of the study on Wikipedia traffic argued the chilling effect of surveillance prevented people from acquiring information they need to make informed decisions in a democracy.

Rayner Fried worries about surveillance cameras having a similar chilling effect at Western, especially considering how difficult it is to get students to show up to events in the first place.

“Sometimes the things you’re doing are pushing the boundaries a bit — and that needs to happen — but knowing that you’re going to be on camera because of that is not a good incentive for people to get out there and do things,” she said.

Concerns about surveillance don’t just come from the university but from external groups too. Samia and another member of SUPER were doxxed — their personal information posted online as a target for harassment — and placed on a list that accused them of racism and supporting terrorism. In June, The Intercept reported the FBI questioned student activists based on their presence on the same list, which is not vetted and is funded by David Horowitz, a racist troll.

Samia worries that, without privacy protections, footage could be used to identify and target student activists.

“We as Arab and Muslim student organizers aren’t safe, and the university should be protecting us before they’re protecting the interests of the FBI or whatever group wants to surveil us,” she said.

SUPER had their own cameras to record what happened at their display, but they draw a distinction between the administration hypothetically recording the display and them doing so.

“They’re in a position of power and for them to be surveilling their own students is, I think, really different than us just keeping a camera to make sure police didn’t aggravate students of color who were working at the wall,” Samia said.

Balancing student privacy with obligations to release footage under Washington’s public records law is one of the potential questions that would need to be considered in any discussions about installing cameras, Rasmussen said.

New Frontiers

Administrators are clear that expanding surveillance cameras on campus would require intense conversations and deep examination of potential implications. However, one area of recently implemented surveillance technology has raised expert concerns.

As part of an upgrade to the digitized parking system in 2016, Western purchased license plate reading cameras for two parking vehicles. The small, boxy cameras are perched on each side of the roof of the vehicle. When activated, they capture the license plates of passing vehicles and feed them to a computer located inside the cab.

Dave Maass, an Electronic Frontier Foundation senior investigative researcher, has monitored license plate readers with his colleagues since 2013. He said the EFF is concerned about the proliferation of automatic license plate reader technology. A big source of their concern comes from retaining the data collected by the readers.

“When they’re going around collecting license plates, what they’re doing is collecting the location of a person,” Maass explains. “They know where the car was, at what time and what date, and they can do that over and over and over again to find patterns of how people move. What time do you come to classes? What time do you leave classes?”

One could track a student or faculty member’s movement by looking at where a certain license plate was recorded. This is problematic for those parked near sensitive locations, like religious centers or queer spaces since the readers could track attendees.

In 2012, the Associated Press reported police in New York City used cars equipped with license plate readers to surveil mosque attendees as part of a program targeting Muslims. A 2015 EFF report Maass co-authored showed Oakland Police disproportionately targeted low-income, Black and Latinx neighborhoods with license plate readers.

Additionally, Vigilant Solutions, a company that operates a centralized database of license plate reader data for police departments and private companies, recently signed a contract with Immigrations and Customs Enforcement. The contract gives the agency access to their data and the ability to be notified if a police department that contracts with Vigilant scans a car they’re looking for, The Verge reported.

Data retention also creates potential for abuse. Someone with access to the system could look up location information inappropriately, an ex-lover or student they have a grudge against, for example. While there is little information on this happening with license plate data, this is an issue with other criminal databases, Maass said.

Other issues with the system are more ideological.

“You have this technology where law enforcement are collecting information on everybody, regardless of whether they are involved in a crime or not,” Maas said. “...That really feels really undemocratic to me, because we live in a society where you’re innocent until proven guilty, the police require probable cause — these are just general, fundamental principles of justice in this country — and to have technology that undermines that, and assumes that everybody's a suspect, and everybody needs things captured on them, is a real concern.”

Western’s cameras, which cost over $96,000 to purchase and install with related software from Canada-based Genetec, are limited to parking enforcement, Rasmussen said. With the new technology, Parking Services is able to go from two sweeps of campus a day to many more.

While data is retained for 30 days, University Police do not use it. A year ago, parking enforcement moved from the Public Safety Department to the Student Business Office. Privacy issues were one of the things looked at when Rasmussen oversaw the system’s installation, he said. They didn’t implement a written policy related to data retention, but there were conversations on the subject.

“We wanted to make sure people felt comfortable that things weren't being retained longer than we needed,” he said.

Rasmussen and Cocke said University Police do not maintain their own list of license plates to track, and the system checks license plates against the Washington State Patrol’s ACCESS database. The database flags stolen cars or license plates wanted for an Amber Alert. Cocke and Rasmussen described this as a safety measure. However, Assistant Director of the Student Business Office Bob Putich said in an email that he is unfamiliar with any database named ACCESS, and Western does not match vehicle plates with any outside database.

The Western Front reached out to Putich for a follow up concerning the ACCESS database, but he was unavailable for comment until a later date.

The question for examining surveillance at an international level are: Is it necessary and is it proportionate? Those questions should apply to use of license plate readers, Maass said. If there is a need for license plate readers, he would like to see transparency in their policies and use, and an assurance they aren’t storing data on innocent people.

As of 2015, California law requires operators of automated license plate readers to create a publicly-available policy consistent with individual privacy and that outlines data retention policies, among other points.

While Western doesn’t currently have such a policy, Lynn Plancich, student business office program supervisor, said they’re working on one — and have since March 2016. The reason it’s taking so long?

“Number one, we had to learn [the system],” she said.