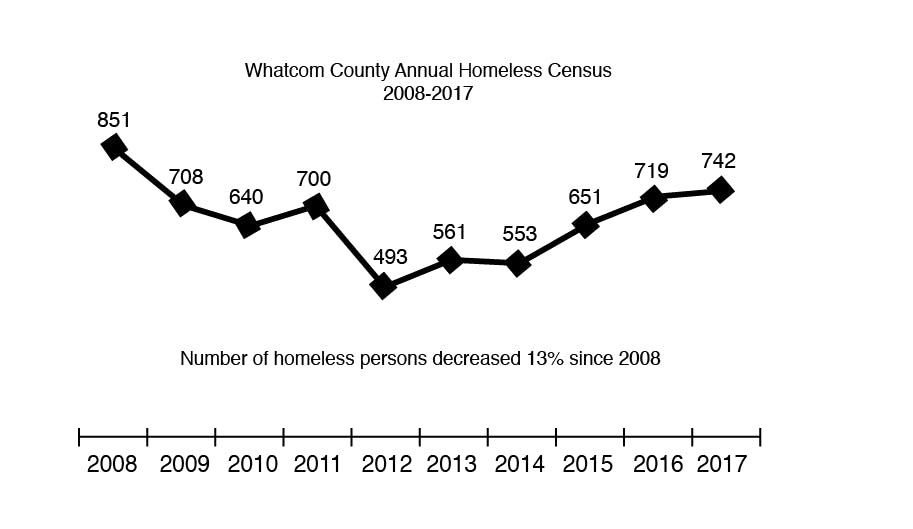

By Roisin Cowan-Kuist The lowest temperature reached this winter in Bellingham was 19 degrees. As weather worsened, local homeless shelters faced overcrowding, leaving many of Bellingham’s residents experiencing homelessness to face the cold and risk death due to exposure. There are around 742 homeless individuals living in Whatcom County, according to a 2017 report from the Whatcom County Coalition to End Homelessness. This number may not include all people experiencing homelessness in the city, the report says, and it continues to rise as the population grows and rental prices heighten. A report by the King County Medical Examiner’s Office found that four percent of homeless deaths between 2012-17 were due to exposure. A similar analysis for Whatcom County has not yet been conducted. There were no recorded deaths due to exposure for people experiencing homelessness in Whatcom County for 2016 and 2017, according to the Whatcom County Health Department spokesperson. However, the department said its data is limited, as whether someone is homeless is not included on death certificates and there is no code for death due to exposure put on death certificates. “I can’t say with any certainty how accurately death records capture the actual number of deaths in Whatcom County of individuals who were homeless,” Melissa Morin, health department communications specialist, said. In January, a man was found dead on a Bellingham beach, after spending the night exposed to the elements, his friends and advocates said. Also in January, the Bellingham City Council passed an emergency ordinance that would establish a set of guidelines for construction of temporary tent encampments on local church properties, bypassing the standard procedure for city ordinances, which can often take months to establish.

“The city just wants them to disappear, and they just keep wasting this money moving people from place to place. And they just end up somewhere else."

Amy Glasser, HomesNow! affiliate

Glasser explained the difficulty in navigating Bellingham’s public camping restrictions. “The city has an ordinance that you can’t camp on city grounds,” Glasser said. “Which means anyone who has no home or who doesn’t want to go to a shelter or was kicked out of the shelter has no choice but to camp illegally or die.” Glasser said she thinks the money the city spends clearing homeless camps would be better spent funding organizations like HomesNow! that provide immediate housing solutions. “The city just wants them to disappear, and they just keep wasting this money moving people from place to place. And they just end up somewhere else,” Glasser said. When asked about the clearing of homeless encampments, Mayor Kelli Linville said rapid population growth and lack of services for homeless individuals has contributed to heightened intervention by law-enforcement. “We tried for a while not cleaning the camps up, letting them go. And that’s when we got the neighborhood complaints about them and the environmental complaints,” Linville said. After the city’s proposed location for a low-barrier shelter was purchased by the Port of Bellingham in May of last year, debates over where to build the shelter prolonged construction of any such facility. The proposed shelter, which would have provided services for up to 200 homeless individuals, was a partnership between Lighthouse Mission and Mayor Kelli Linville. “The challenge is finding a place to site this particular shelter,” Hans Erchinger-Davis, the executive director of Lighthouse Mission, said. Erchinger-Davis said shelters should not be too close to residential or storefront areas because of perceived impact on businesses and neighborhoods.“We hear a lot of not understanding of the nature of disabilities. And a lot of the folks who are actually experiencing homelessness have some pretty severe care needs."

Mike Parker, director of the Whatcom Homeless Services Center,

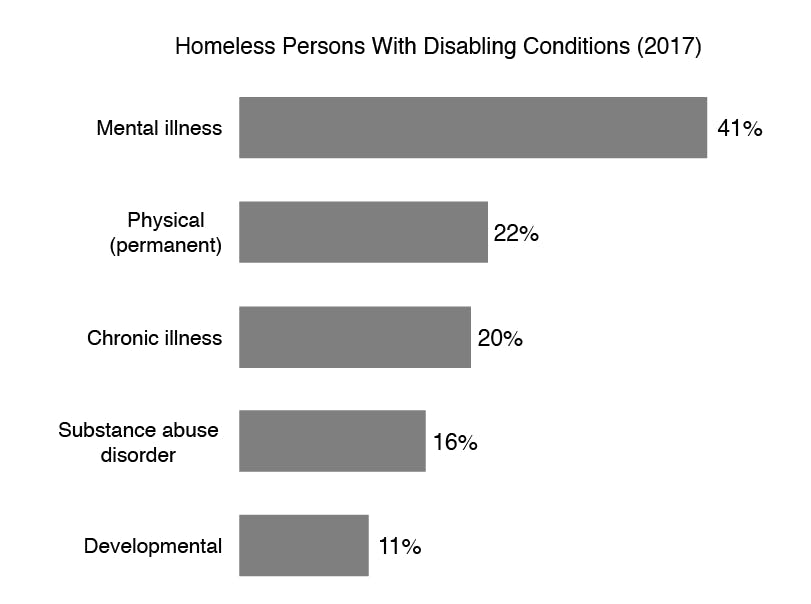

Advocates in the community have taken to social media to urge city officials to provide regulated campsites in the meantime, as well as basic sanitation and waste services. “The advocates would like us to build tiny homes, and we are open to allowing that to happen,” Linville said. Linville also addressed concerns surrounding sanitation and hygiene services were those sites to be built. “We will supply dumpsters and porta potties,” Linville said. “But right now nobody is willing to let any organization that can’t manage it to build tiny facilities on their property.” Other community officials maintain that homeless encampments do not provide a sustainable solution to the homelessness crisis. “In my opinion, a tent city is one of the worst ideas you can pull together,” Erchinger-Davis said. “The only time a tent city is ever good is if there's no capacity for a shelter.” Mike Parker, director of the Whatcom Homeless Services Center, said homelessness disproportionately affects those who are physically or mentally disabled, veterans, survivors of domestic abuse and those who are economically disadvantaged, among other marginalized groups. “We hear a lot of not understanding of the nature of disabilities. And a lot of the folks who are actually experiencing homelessness have some pretty severe care needs,” Parker said. Others don't agree. “Nobody has to be homeless,” Pastor Timothy Whiteman said. “Between the drop-in center and the other churches, they were never full. They always had beds available. The people who were on the streets chose to be there because they wouldn't go with the low barrier requirements.” However, Lighthouse Mission Ministries’ drop-in shelter that has capacity of 120 people per night, compared to the 742 people experiencing homelessness counted in the 2017 point-in-time count. Glasser said the shelters do not always have the capacity to provide for all those who need it, and people are often turned away for a number of reasons, including addiction and mental health conditions that can cause violent outbursts. Erchinger-Davis said other mental health conditions may cause certain individuals to view the Mission’s services as inaccessible. “Some people have social anxiety and they don’t want to come to the drop-in center program because there’s a lot of people there,” Erchinger-Davis said. Glasser also said that because the Lighthouse Mission is a Christian organization, LGBTQ+ individuals experiencing homelessness and those who practice other religions may not feel welcome at the Mission.“Just because we can’t solve the problem immediately, doesn’t mean we don’t care about it or that we aren’t trying to find a solution."

Kelli Linville, mayor of Bellingham

Other activists argue that lack of regulation of local shelters leads many homeless residents to risk the streets over staying in a shelter. “No investigatory process or audit has been made either to deny or confirm the safety hazards at the Mission,” Christine Mansfield, a volunteer with HomesNow! Not Later, said over email. “The Mission is technically an independent, tax-exempt agency not beholden to city, state or federal regulatory action.” Peter Hansen, the ministries manager at Lighthouse Mission, said while it’s true the facility does not undergo an annual audit of their safety procedures, safety is still a top priority. “I would like us to be in the mindset of always being ready to be audited, period,” Hansen said. Hansen explained the Lighthouse Mission is working to improve their drop-in center’s safety by remodeling the entry to have more checkpoints and security doors. “We face the same problem that other communities in the Puget Sound face, which is just a real scarcity of affordable housing,” Parker said. “And the people that experience it the worst are the people on the streets. It’s a lot harder for them in the rental market.” Recent community housing projects such as 22 North and Francis Place provide relief to some of Bellingham’s most vulnerable residents experiencing homelessness, Teal Coyote, housing services supervisor of Francis Place, said. Francis Place partners with the Opportunity Council and the Homeless Service Center, providing 42 units of permanent housing and operating on a referral-based system to determine who is given permanent residence. “Francis Place gets the referrals from the Homeless Service Center that are the most complex health needs,” Coyote said. “It’s really the people who are definitely chronically homeless, which is a definition that includes the length of time somebody is staying outside or in emergency shelters, and also includes disability.”